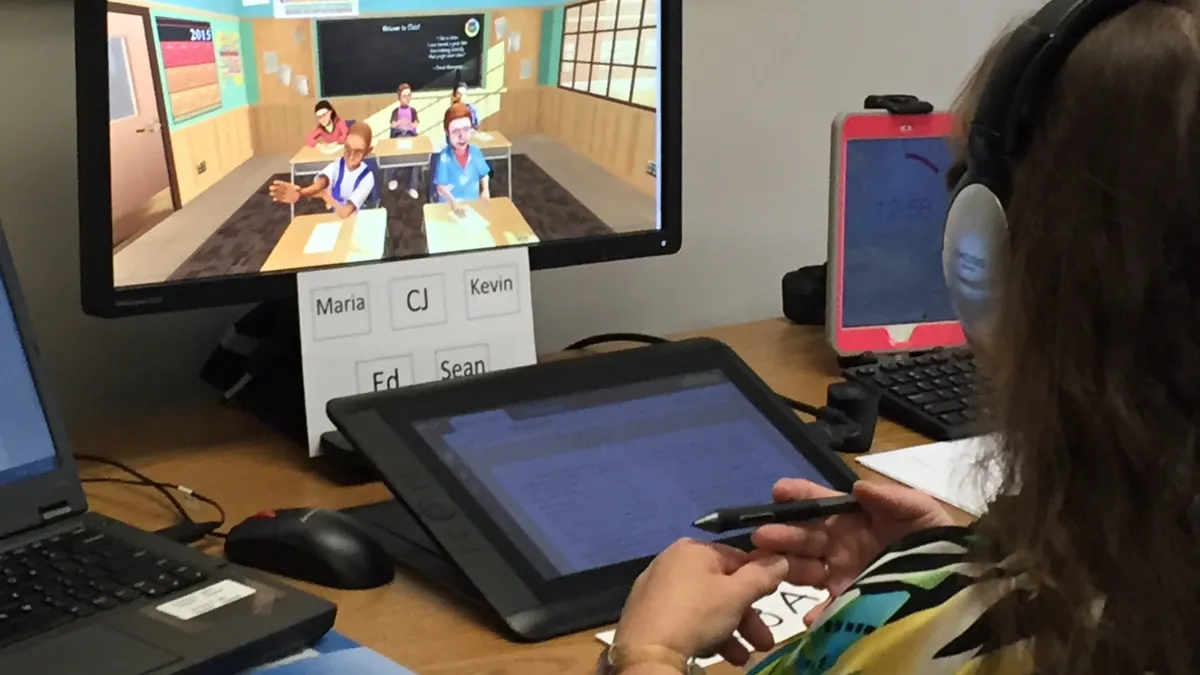

A prospective elementary teacher sits down to work with a student on a mathematics problem. In this case, though, the student appears on a computer screen as part of a real-time simulation. Much like an elementary student, a third-grade student in the simulated classroom interacts with you as you pose questions, allowing you to respond to what the student says, interpret responses to the students’ ideas, and move the interaction forward in relation to an instructional goal.

The intriguing question here is: How does the student “know” how to respond? The answer involves an innovative approach to assessment, in which the student is controlled by a carefully trained adult known as a “testing simulation specialist.” This new technology is being developed through a partnership joining Educational Testing Service (ETS), TeachingWorks at the University of Michigan, and Mursion, a technology firm that provides a virtual training platform for teachers and principals to practice and master essential skills.

Mursion’s forerunner, TeachLivE™, has been using these customized training simulations for some time now in the context of teacher preparation. What’s new is their use for teacher licensure. These simulations are being used as part of ETS’s new teacher licensure assessment, the National Observational Teaching Exam (NOTE). Two key teaching practices — leading a class discussion, and eliciting and interpreting individual student thinking — involve real-time simulations. Assessment tasks for each practice have been developed for the lower and upper elementary grades in mathematics and English language arts.

The use of simulated classrooms and simulated students to assess teaching practices builds on the approach used in medical licensure of asking prospective doctors to undertake an examination with live but simulated patients. In the medical case, the candidates have to come to where the patients are. Using simulated classrooms and a set of testing simulation specialists, our approach allows us to bring the classrooms to the candidate. A prospective teacher can be “dropped into” multiple classrooms and multiple instructional situations, with the testing simulation specialist working to ensure — like the standardized patient — that all candidates are faced with the same kinds of opportunities and challenges when asked to show what they can do.

Testing simulation specialists are trained to follow each candidate’s lead during the performance. They practice on the specific tasks they enact and are rated via a rubric designed to capture key aspects of their performance. The testing simulation specialists follow a set of guidelines that balance the need for standardization with responsiveness to the candidate’s instruction. They also must pass a test to be certified and undergo periodic recertification testing.

In interacting with students in lesson segments ranging from 10 to 15 minutes, the candidate has access to tools for use in writing or drawing; the testing simulation specialist also has access to these tools. Interactions in response to instructional tasks are both verbal and physical, capturing what candidates say and do in response to what simulated students say and do during the lesson segment.

Other fields, particularly medicine and nursing, make extensive use of simulations in training and assessment for several important reasons. One is that students can practice repeatedly on a skill and receive targeted feedback. Another is that simulations protect patients and clients because “practicing” on clients may cause harm. Candidates learn skills before they begin interacting with patients or clients. This innovative assessment points the way to expanded uses of simulations in the educational field as a key component in the process of preparing teachers and assessing their competence in critical practices of teaching.

To learn more about NOTE, visit ets.org/note