On a recent visit to a college, Alexandra Brodsky encountered a group of students protesting Title IX who wanted it abolished.

Brodsky, an attorney at Public Justice, a legal advocacy organization, figured out quickly the students weren’t actually seeking the elimination of the linchpin federal law that protects against sex-based discrimination and sexual violence in schools. The demonstration represented their frustrations with the Title IX processes at that college, which Brodsky declined to name.

The protesters believed the institution had failed to adequately address alleged sexual misconduct, inaction that Brodsky said in part can be traced to a federal Title IX regulation enacted under the Trump administration, which narrowed the scope of cases colleges are required to investigate.

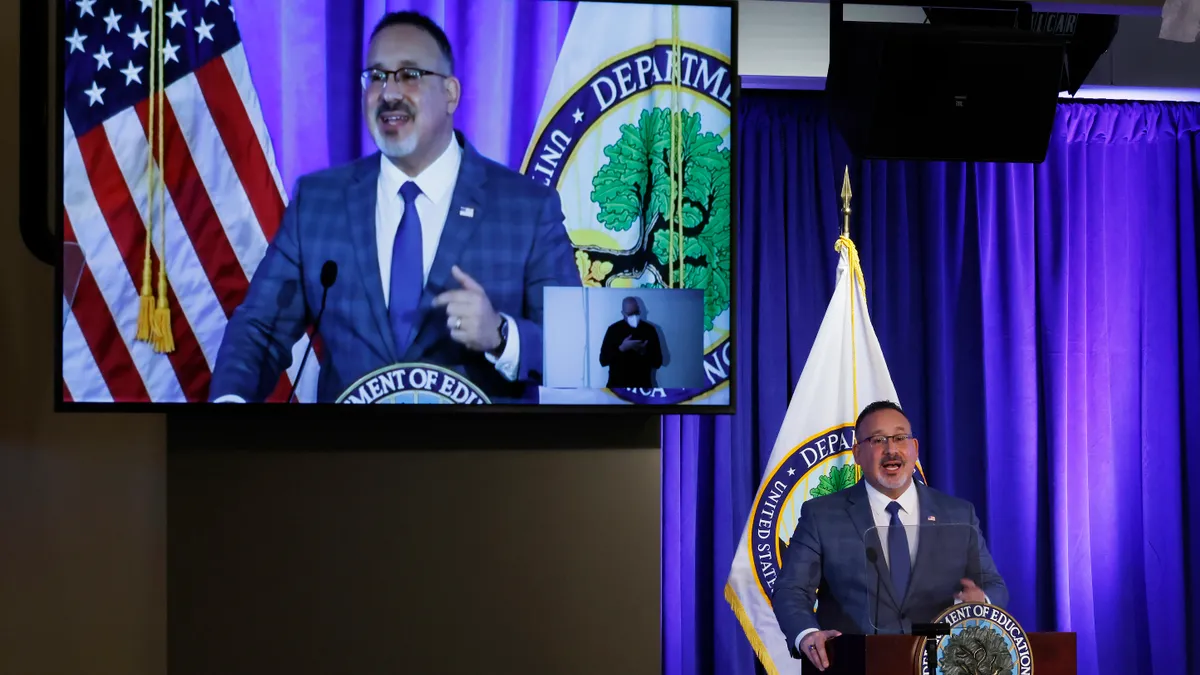

The U.S. Department of Education under President Joe Biden is due to replace the Trump-era rule, but his administration has postponed issuing a regulatory plan twice. The proposal is now expected this month.

A consequence of those deferrals is students’ eroding faith in procedures intended to safeguard those who have experienced sexual violence, Brodsky said. Advocates for sexual assault survivors deride much of the Trump administration’s rules, which they say dissuade reporting.

Continued delays have other repercussions. Federal mandates that the Education Department review public comments on the draft rule mean it may not take effect until a year or more after the agency releases it. In the interim, campus Title IX coordinators and other administrators are left upholding a regulation they know the Education Department will scrap, even as they brace for changes to come.

Congress also has authority to overturn major regulations, and a new Republican majority, which is possible after the November midterm elections, could pursue this option, depending on when the department finalizes the rule.

Rapid regulatory changes

Over the past 11 years, Title IX has undergone an elaborate policy overhaul, beginning in 2011 when the Obama administration put forth guidance that directed how colleges should investigate and potentially punish sexual violence. Though the guidance was largely rooted in court precedent, it spurred a much more politicized era of Title IX than in previous years. Criticism followed that the federal government pressured colleges to find accused students responsible for sexual misconduct and that institutions were trampling their due process rights.

Former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos seized on the complaints to devise the current rule, which took effect in August 2020, more than a year after she introduced a proposed version. It most notably constructed a judiciary-like setting to evaluate sexual misconduct reports, and it enabled accused students and their accusers to cross-examine the other side through advisers.

Though DeVos’ rule has been subject to many legal challenges, courts have almost entirely preserved it. That’s except for one provision that colleges during the hearings could not consider statements made by parties or witnesses who did not subject themselves to cross-examination.

Biden on the campaign trail had promised to unravel the current regulation and formally announced in June 2021 the administration would rewrite it. Initially targeting an April 2022 release date for the draft rule, the Education Department has twice pushed back its publication and intends to issue it this month.

Title IX will reach its 50th anniversary on June 23, the date it was enacted in 1972. It historically has sought to ensure sex-based equity in academics and athletics. The Biden administration is reportedly eyeing an expansion of those protections to transgender students.

Why the delays?

Possible inclusions in the regulatory proposal that will prove controversial — like new safeguards for transgender students — might partially explain the Education Department’s delay, said Jake Sapp, Austin College’s deputy Title IX coordinator and compliance officer, who tracks legal matters concerning the law.

Opponents of the rule are already threatening lawsuits against it, such as 15 Republican state attorneys general, who in April wrote to the Education Department, requesting it halt the rulemaking process. They particularly took issue with the reported transgender student protections, writing they were “prepared to take legal action to uphold Title IX’s plain meaning and safeguard the integrity of women’s sports.”

The Education Department will want to ensure the rule survives court challenges, Sapp said, which entails a lengthy process of writing out justifications for why provisions of the regulation are needed. Otherwise, a judge may find portions of the rule arbitrary and capricious, he said.

“If they skip that meticulous analysis, they could potentially lose that piece of the regulation,” Sapp said.

The Education Department did not immediately respond to a request for comment Friday.

What could happen?

However, the Education Department risks Congress retracting the rule entirely if the agency waits too long to release it, Sapp said. The Congressional Review Act gives lawmakers power to reject major executive actions within 60 days of final rules being submitted to the chambers.

And the procedures for finalizing a rule are cumbersome. The Education Department is legally obligated to respond to public comments that will be submitted once the draft rule is released, Sapp said. The department doesn’t have to address the comments individually, but the rule’s final iteration must touch on them all, he said.

A deluge of comments was thought to have contributed to a drawn-out timeline for DeVos’ rule being established. The department under DeVos first issued a draft rule in November 2018, but the final version wasn’t published until May 2020, after the department received more than 120,000 public comments.

The Trump administration had also feared Democrats would try to capitalize on the Congressional Review Act to overturn its regulation.

If the Biden administration’s rule follows the same timetable as DeVos’, and it puts forth a draft rule this month, a final regulation may not come to fruition until 2024, toward the end of the president’s first term.

This could mean the rules' future hinges on who controls Congress after this year's midterms.

The interim period

As the department juggles policy considerations, college administrators are taking varied approaches to enforcing the current rule, said Brett Sokolow, president of the Association of Title IX Administrators.

While institutions legally must follow the regulation, they can “take it with a grain of salt,” Sokolow said. That might include actions like funneling minor offenses through a college’s disciplinary code rather than Title IX proceedings, he said.

“It doesn’t make sense to go through a four-month extremely bureaucratic process for a butt touching,” Sokolow said.

Sokolow and his organization are also trying to educate officials. Some colleges lack knowledge about regulatory proceedings, and the association gets “a decent number of calls” asking about the fallout when a new rule takes effect this June — a significantly incorrect timeline, Sokolow said.

“They’re just kind of waiting around for what this next round will be,” he said.

Lance Houston is a lawyer who founded University EEO, Inc., a Title IX consulting firm, and now works as a managing director and Title IX coordinator for Capitol Region Education Council, a Connecticut-based agency that helps support local K-12 schools.

Houston said he believes the Trump administration’s rule will “have a lasting effect” on future Title IX regulation, including what Biden’s Education Department produces. He said that the Biden administration will want to maintain certain due process protections. Houston also doubted the White House will mandate a legal evidentiary standard.

Under the Obama guidance, colleges were required to use a “preponderance of the evidence” standard, which means a greater than 50% chance that a claim is true. That's a lower bar for accusers to clear than the higher “clear and convincing” standard. The Trump rule allows institutions to choose either.

“This all will impact regulatory approaches for years to come,” Houston said.