More regulatory oversight and competition with public colleges could be in store for the for-profit sector under the Biden administration.

The president-elect is expected to revive key Obama-era regulations on for-profits, and he has pledged to fund free college initiatives at public two- and four-year schools. That's in addition to other proposals to give more money to private nonprofit and public colleges.

How the administration will carry out its plans, and to what extent, depends partly on whether Republicans keep Senate control. And it's early in the transition, so much of what comes to pass for the for-profit sector will depend on who fills key leadership roles at the U.S. Department of Education, higher education observers say.

The for-profit sector has also changed over the past several years, with the number of institutions and enrollment shrinking largely as a result of prior regulations that raised the bar on student outcomes. Some large for-profit college operators, meanwhile, have taken up a new business model that sees them offering services to colleges rather than running them.

"For the past four years (for-profits have) had a nice landscape to where they, I think, have felt pretty comfortable," said Wesley Whistle, senior adviser for higher education policy and strategy at New America, a left-leaning think tank.

Competition from publics

One hallmark of Biden's higher ed proposal is a pitch to make community colleges tuition-free to all students and public four-year schools tuition-free for students whose families earn below $125,000, with states footing some of the bill.

It'll need Congressional approval, however. That step, along with the hit state budgets are taking, could make the proposal less likely to move forward, at least in full form. But it stands to affect for-profit colleges if it does, said Jeff Silber, managing director at BMO Capital Markets.

"Any time there's more funding for the nonprofit sector that's not available to the for-profit sector, that obviously adds competitive pressure," Silber said.

More investment in community colleges has been tied to a shift in students to those schools from for-profits, said Stephanie Cellini, a professor of public policy and economics at George Washington University. Cellini's research also found that enrollment shrinks at for-profits and grows at nearby public colleges when the former is at risk of losing federal aid.

"The for-profit sector has a massive marketing budget that they can use to recruit students ... if we made public community colleges, or public colleges generally, tuition-free, that's gonna be a public awareness issue that will overcome that marketing budget," Whistle said.

Other changes, such as Biden's proposal to double the maximum value of the Pell Grant, aren't guaranteed to draw more students to for-profits. They were left out of some versions of legislation proposed last year to expand the Pell Grant.

'We do a much better job'

Biden is expected to bring back versions of two Obama-era rules that target for-profits, which the Trump administration rolled back. They focus on the return on investment students get for their education. But reinstituting those policies, even through executive action, could take time. And one of them — the gainful employment rule — would likely go through a lengthy rulemaking process, Silber wrote in an analyst note earlier this month.

The president-elect has also said he will put forward legislation to close a loophole in the 90/10 rule that lets for-profit colleges exclude military benefits from their calculation of how much of their funding can come from the federal government. For-profits get a disproportionate share of service members' and veterans' education benefits.

Steve Gunderson, the outgoing head of the top for-profit college trade group, argues the for-profit sector has changed since the Obama years, when Biden was vice president.

The for-profit sector would be willing to work with the Biden administration to come up with "ordinary, appropriate policy" for students who believe their colleges defrauded them, and to figure out a "fair and equitable formula" for the debt-to-income ratios in the gainful employment regulation, Gunderson said. His organization has not yet put out a proposal for what that work could entail.

"Our sector is incredibly different today than it was at the height of the Great Recession. We are smaller, but we have a much higher focus on outcomes, and we do a much better job," Gunderson said.

Cellini points to fall enrollment as a potential cause for concern, however. Preliminary data shows overall undergraduate numbers down, particularly at community colleges, while four-year for-profits are on par with levels a year ago. To Cellini, it's "a signal that this relaxed regulatory environment of the last several years has kind of allowed (for-profits) to grow and thrive on potentially their old business models."

For-profit enrollment climbed during the last recession, when colleges overall saw a bump in students entering their programs. The fall data shows strong enrollment gains at primarily online colleges, with most schools in that subset being four-year for-profits.

The sector may be trying to make bipartisan inroads. Gunderson's organization, Career Education Colleges and Universities, recently selected a former Democratic congressman as its next president and CEO.

OPMs and nonprofit conversions

For-profits' interests are also increasingly tied to another piece of the higher ed sector: online program managers. OPMs provide colleges with a range of educational services, and they are under scrutiny by Congressional Democrats over whether the way many of their college customers pay them violates federal law.

Some for-profit college operators, including Zovio (formerly Bridgepoint Education) and Grand Canyon Education, have or are in the process of separating their colleges and becoming OPMs.

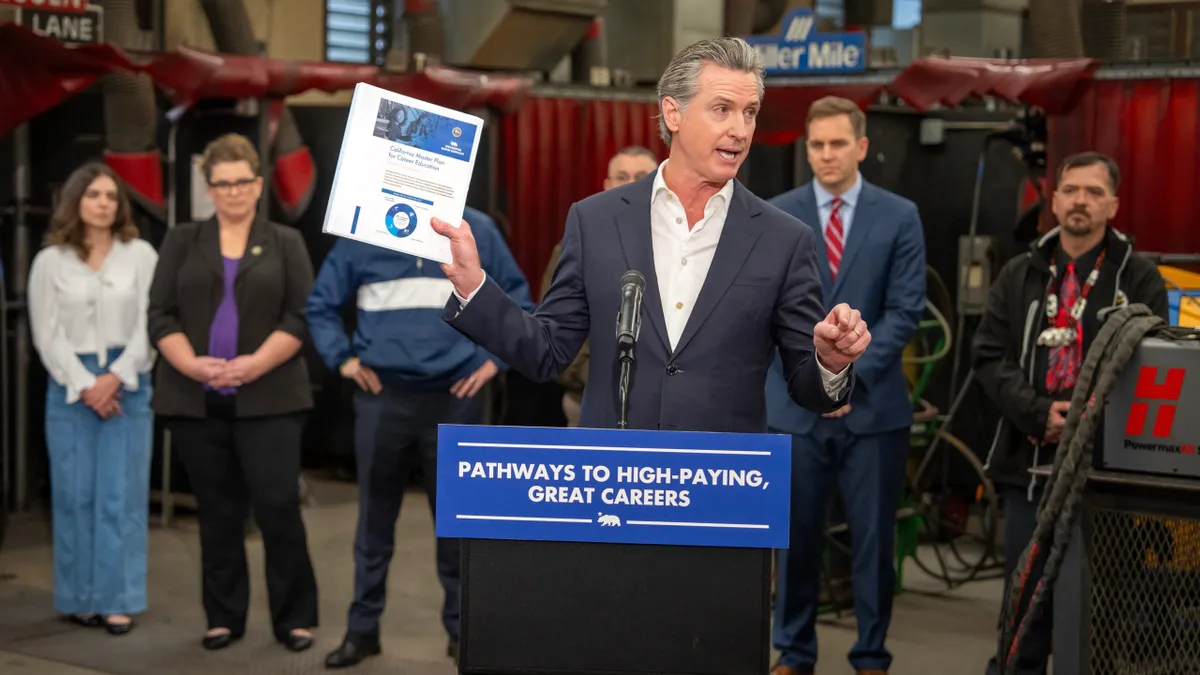

The model has its share of detractors, including The Century Foundation, a left-aligned think tank that has called into question the fairness of OPMs' contracts with colleges. Bob Shireman, a senior fellow at the foundation, also has questioned whether elements of the relationship are solidly in line with federal law. And he helped write legislation that attempts to crack down on the sector in California.

So it's "an alarming sign" for the for-profit sector that a Century Foundation representative is on Biden's education transition team, said Trace Urdan, managing director at investment bank and consulting firm Tyton Partners, which studies OPMs.

BMO's Silber thinks the pandemic may have lessened lawmakers' interest in going after OPMs, citing an uptick in online learning and cash-strapped colleges' need for capital to add virtual offerings. But Silber writes that the popular payment structure in which colleges give OPMs a cut of tuition revenue to pay that upfront investment "may face continued scrutiny."

A crackdown on the sector could shift the tuition revenue-share payment model to one in which colleges pay for services as they are provided, Urdan said, an option that is becoming more popular. But one of the revenue-share model's advantages is that it gives colleges money to launch a program. In its absence, Urdan expects third-party groups would step in with capital to help colleges.

But those funders may not be as interested in smaller schools or ones using online programs as a last-ditch effort to stay in business. And regulatory involvement may sour some investors on the sector.

"The freedom from the regulatory elements of proprietary schools was considered one of the great investment features of this sector, and if that goes away, that's going to hurt their ability to raise capital," Urdan said.