The end of the 2023-24 academic year came to a dramatic close for the scores of colleges challenged by widespread campus protests and student activism over the Israel-Hamas war. But one institution, Columbia University, found itself at the epicenter of the movement, eliciting echoes of the Ivy League institution's complex history with campus activism.

Long home to countercultural ideas and demonstrations, higher education institutions grappled with pro-Palestinian demonstrations and counterprotests following the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel that reignited the calamitous war. Students — sometimes with support from faculty — built encampments, demanded a cease-fire and called upon their institutions to divest from companies with ties to Israel.

With the war raging on, student protests are likely to erupt again this fall. In turn, policymakers and the public will likely continue to scrutinize college leaders for how they handle these demonstrations. Former Columbia President Minouche Shafik recently resigned amid backlash to her decisions, as did the leaders of Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania.

"Columbia has not been a very good school for free speech — not historically, not currently,” said Zach Greenberg, faculty legal defense and student association counsel at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. “Especially not in recent months.”

When asked about its free speech culture and policies, Columbia directed Higher Ed Dive to a recent statement by Dr. Katrina Armstrong, the university’s new interim president.

"We must continue Columbia’s long history of rising to meet the moment, of educating and training the world leaders of tomorrow," Armstrong said in an August statement. "Freedom of inquiry, speech, and debate are essential to that mission. We must take care to bridge divides, find common ground, define our rules and their consequences, and reach understanding based on our shared values.”

Battles over free speech are not new to the 270-year-old university. Columbia faced similar uproar in 1968, when students held extensive demonstrations and sit-ins to protest the Vietnam War and call for civil rights.

We’re looking back at how Columbia handled demonstrations during the spring term, and how those events parallel protests that rocked the campus 56 years earlier.

Columbia now

Protesters at Columbia set up an encampment on the university lawn on April 17, demanding that the university call for a cease-fire and divest from companies that do business with Israel, including weapons manufacturers.

Their protest gained national attention and spurred students at other universities to form encampments. From April 12 to May 13, police arrested over 2,950 people at pro-Palestinian protests across at least 61 campuses, per Axios. And by May 6, roughly 140 colleges had seen demonstrations, according to the BBC.

The day after Columbia protesters erected their encampment, university officials called in the New York Police Department to disperse the crowd, a rare move for the private institution. Police arrested over 100 people.

The unrest also caught the attention of Republican lawmakers, many of whom accused Shafik of not doing enough to protect Jewish students from antisemitism. Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, flanked by Republican legislators, called for her to step down “if she cannot immediately bring order to this chaos,” during a press conference April 24 at Columbia University. Johnson later pressured Columbia's trustees to remove her from office.

But soon after the first round of arrests, protesters rebuilt the encampment, where it stayed until April 30.

That day, protesters occupied the university's Hamilton Hall after Shafik announced the university would not divest from companies with ties to Israel. Columbia had negotiated with protesters for days "to find a path that would result in the dismantling of the encampment and adherence to University policies going forward," Shafik said in an April 29 statement.

No agreement was reached, and Columbia brought in police to clear the encampment. Officers again arrested more than 100 people. Afterward, a University Senate report concluded that Columbia had broken its own rules by overriding the group’s rejection of bringing police onto campus to deal with the protesters, according to Fortune.

“It could have been handled in a much better way, with clear rules enforced evenhandedly,” Greenberg said. “But because the university didn't really abide by its own policies, it resulted in a lot of negative news coverage and a pretty egregious violation of students' rights.”

The more things change, the more they stay the same?

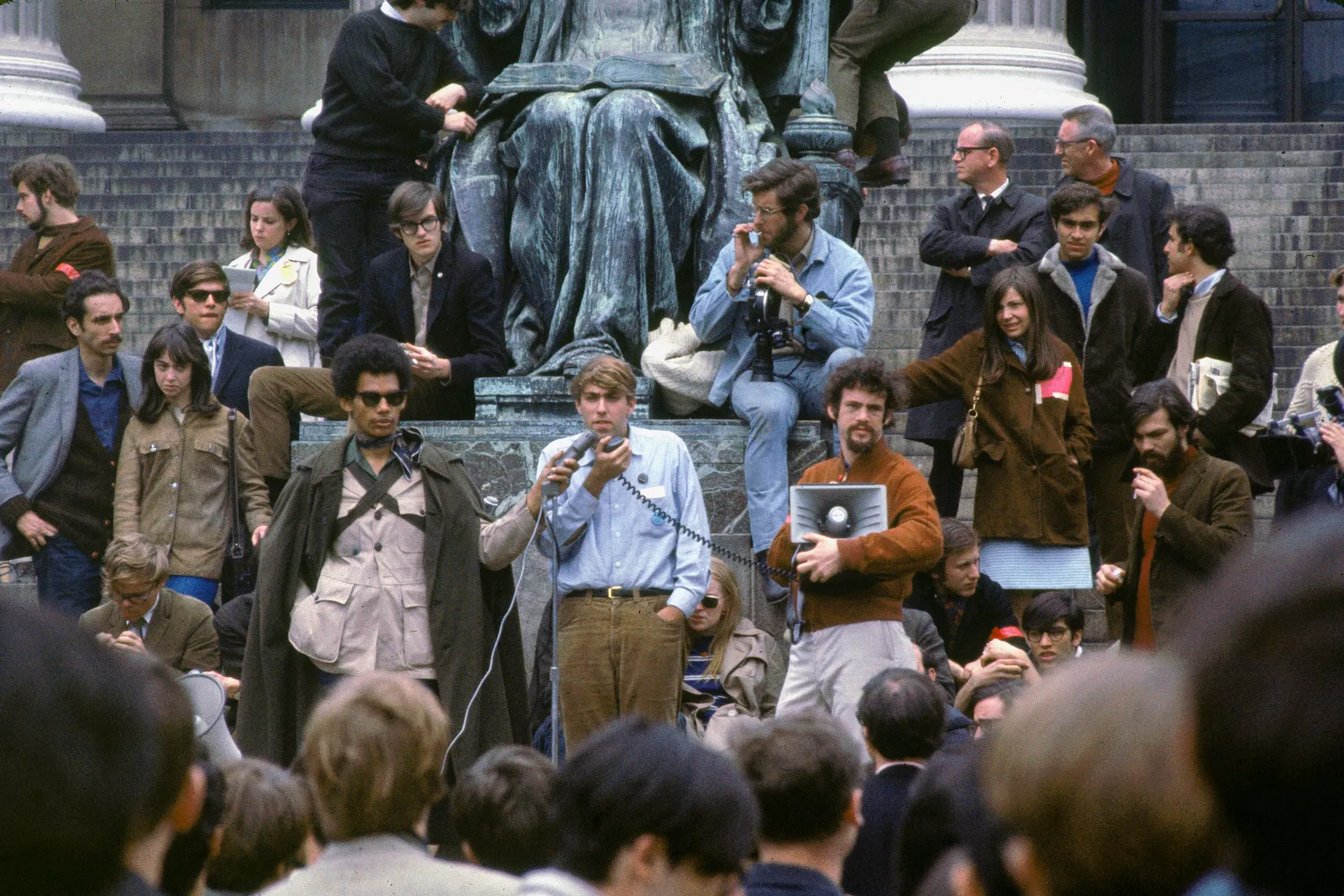

Fifty-six years ago, Columbia also became a hotbed of student protest. The times were different — the student body was less diverse and protesters and onlookers didn’t have almost ubiquitous access to recording devices — but one of their causes was the same: protest against an unpopular war being fought on foreign soil.

During the Vietnam War, the rising death toll of American soldiers partly fueled the protests. Now, students are largely protesting the U.S.'s military aid for Israel in its war.

That year, 1968, also marked the last time Columbia called in police to deal with protesters. And it was a decision that university leaders later said took years to recover from.

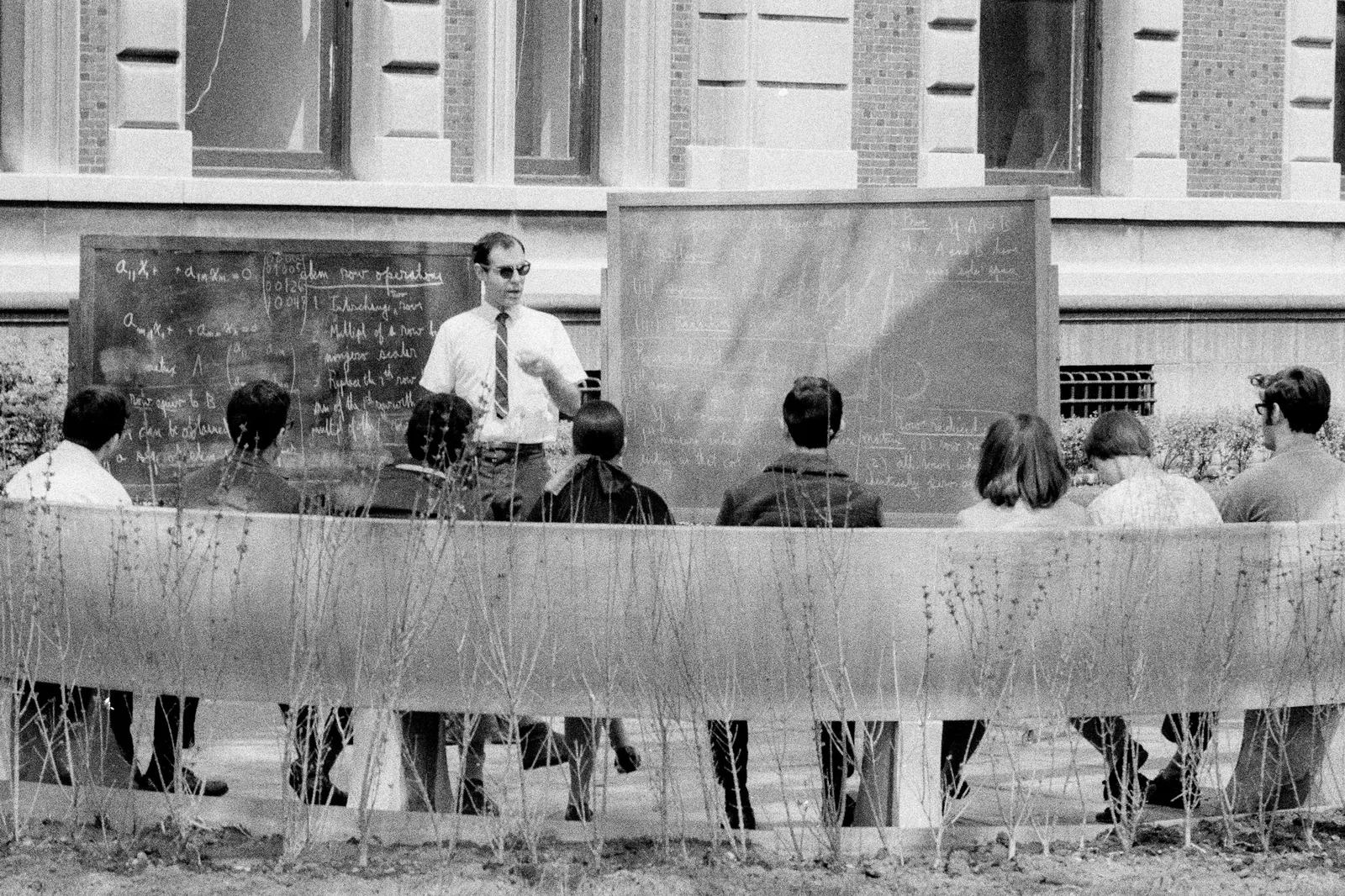

During the height of the Vietnam War, Columbia became a flashpoint for anti-war and anti-racist activism. Columbia students protested the war, the university’s ties to military research, and plans to build a private gym in a public Harlem park with limited community access. The project represented Columbia's increasing presence in the area, which critics argued displaced the largely-African American residents.

Columbia has since enshrined the protests and sit-ins known as the spring ‘68 student uprising into its institutional history. It commemorated the 50th anniversary in 2018, including with an online archive that collected interviews and documents from the period. And yet the unfolding of events and the institution's response foreshadowed how the pro-Palestinian protests would play out almost 60 years later.

In April 1968, protesters occupied five campus buildings, including Hamilton Hall and the president's office, holding a dean in his office for 24 hours.

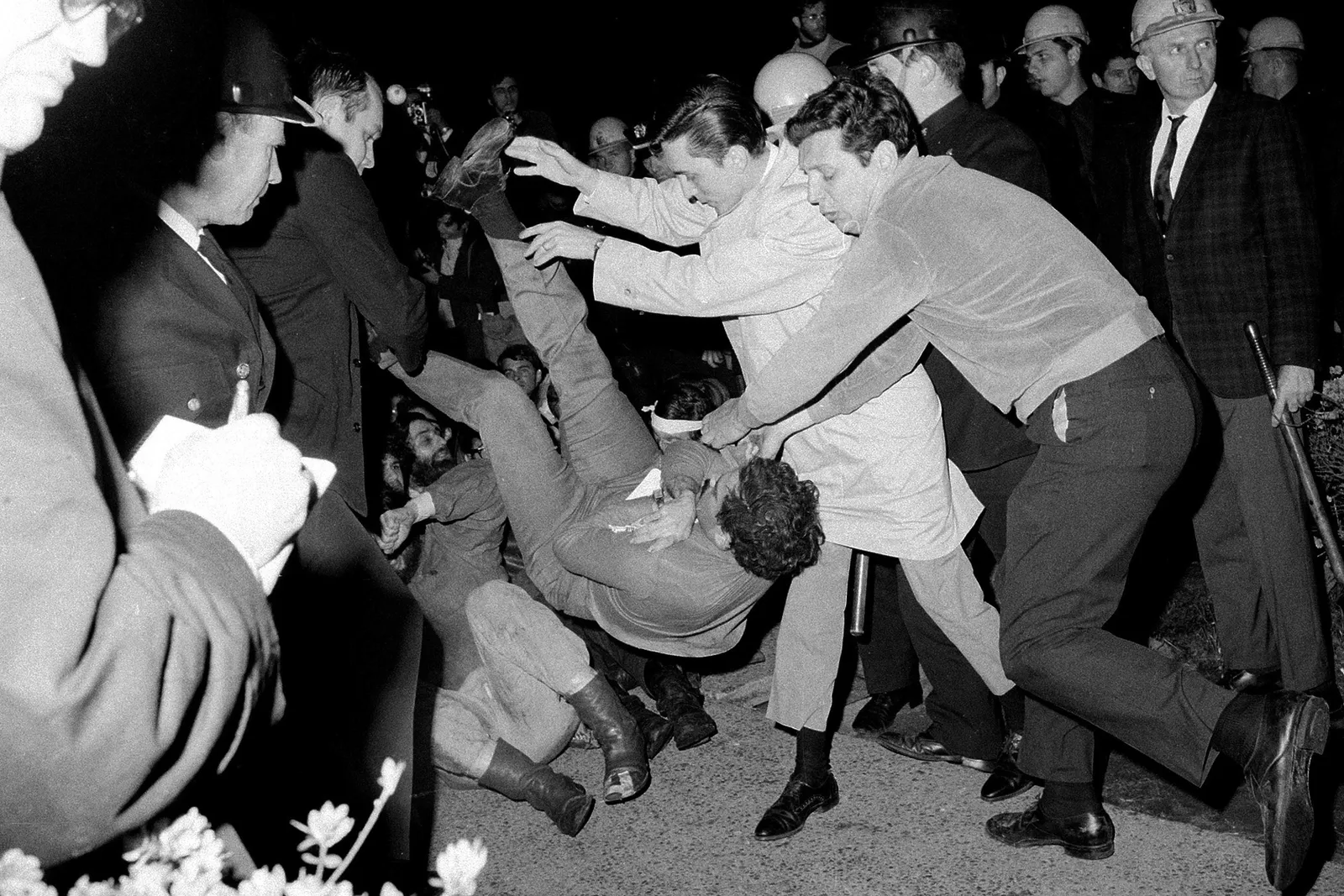

University leadership called in the police on April 30, a week after students occupied the buildings. It would be 56 years to the day when university leaders would call police to the campus again to handle protesters.

"After a weeklong standoff, New York City Police stormed the campus and arrested more than 700 people," Columbia said in its 2018 retrospective of the 1968 events. Amid the arrests and clashes, 148 people were injured.

"The fallout dogged Columbia for years," the university said in 2018. "It took decades for the University to recover from those turbulent times."

What's past is prologue

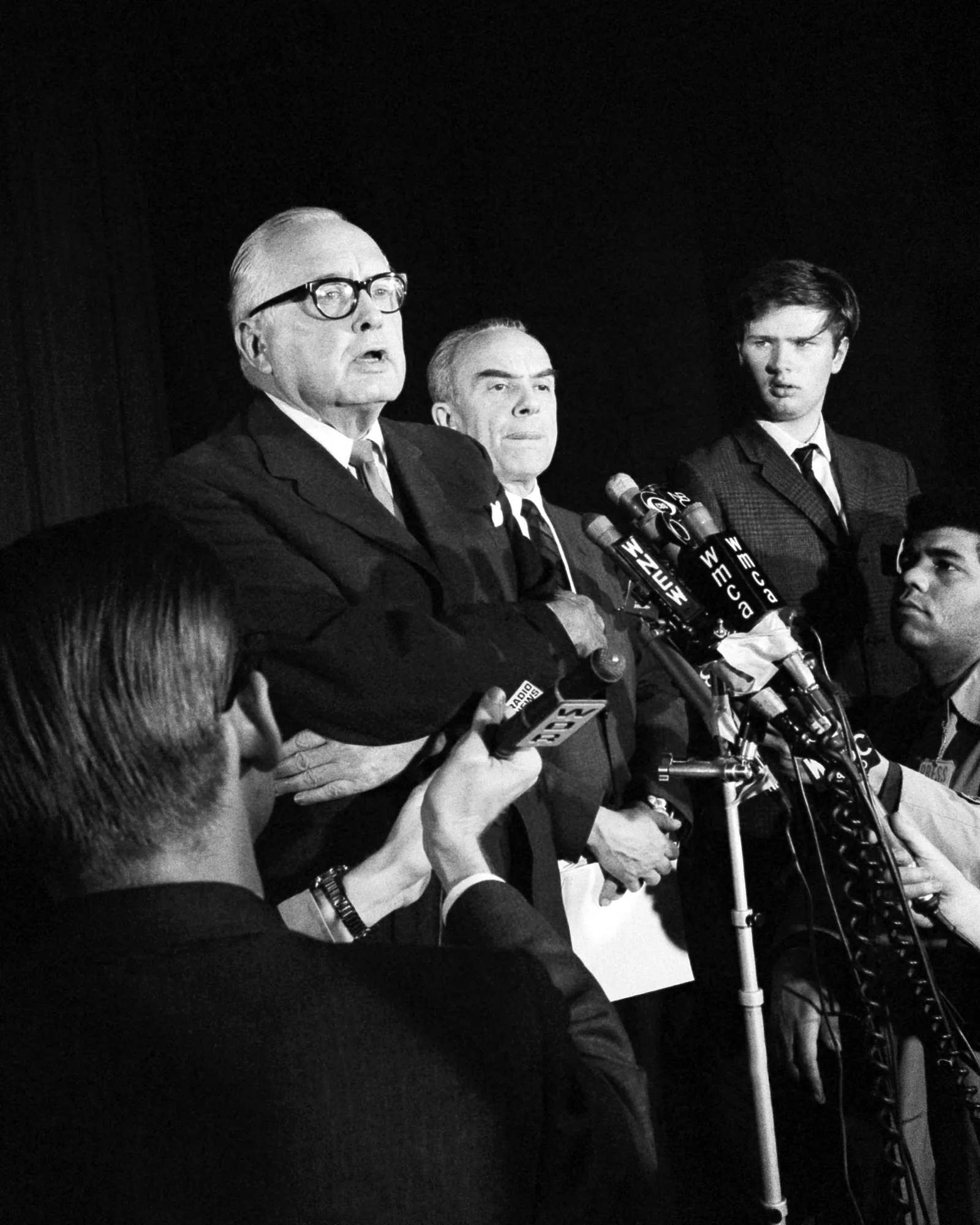

Following the 1968 unrest, then-President Grayson Kirk resigned in August amid accusations that he mishandled the situation by involving the police. He initially resisted calls to step down.

The university “has been paralyzed by the illegal acts of a minority of its students, aided and abetted by an unknown number of outsiders," he said during a news conference after he called in police.

But Kirk ultimately acquiesced in the hopes that his retirement would ensure “the prospect of more normal university operations," he said.

Faculty members in both 1968 and 2024 criticized the university for opening the campus to the NYPD.

Like Kirk, Shafik withstood calls for her resignation for several months. But ultimately, pressure from both supporters and critics of the protesters led Shafik to step down in August.

But the changes in leadership following this year's demonstrations and those that took place almost 60 years ago seem to be where the two events diverge.

Following the 1968 protests, the university ended its involvement with classified war research and halted military recruitment on campus. It also ended construction on the contested gym in Harlem.

Columbia has not reached a similar deal with protesting students this time. In spring 2024, university administrators met with pro-Palestinian protesters, but did not reach any concessions by the time the academic year ended.

The 1968 demonstrations also resulted in changes to Columbia's governance structure.

In an April 1969 campus referendum, Columbia students and faculty overwhelmingly voted to establish a University Senate. The new governing body is composed of faculty, students, alumni, administrators and other stakeholders.

But in 2024, the same body unanimously voted to deny an administrative decision to bring police onto campus to handle demonstrating students. During the spring term, the University Senate ruled that Columbia had violated its own rules by overriding that vote and bringing in police anyway.

The fall return to campus

Given that the conflict in Gaza continues unabated, college leaders can expect the unrest of the spring 2024 semester to continue as classes resume for the fall. The presidential campaign and November elections are likely only to supercharge the rhetoric and protests, Greenberg said.

“All colleges would be wise to prepare, to have their policies in order and to expect students to exercise their free speech rights,” he said.

Use of those rights can be expected to lead to disagreements, Greenberg said. He noted that universities may have had more homogenous student bodies back in the ‘60s and ‘70s. But college is now accessible to more students, and some campuses may have larger populations.

All colleges would be wise to prepare, to have their policies in order and to expect students to exercise their free speech rights.

Zach Greenberg

Faculty legal defense and student association counsel at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression

“That creates a lot more diversity in terms of the political viewpoints that are on campuses,” he said. One college can have hundreds of student groups, each with their own agendas.

The current generation of college presidents and top officials may not have previously seen this degree of protesting during their tenures, said John Thelin, professor emeritus of higher education at the University of Kentucky

“They were very much caught unawares,” he said.

But using what they learned in the spring, leaders need to set clear expectations and consistently enforce whatever rules they put in place, Thelin said.

“Personally, I don’t love the idea of permitting camping overnight on campus,” Thelin said. “But if that’s something you allow, you have to be clear and consistent about what that rule entails."

That transparency needs to come into play prior to policies being formalized, Greenberg said.

"People should be able to comment on them and understand why they're there, not just that they exist," he said.