Publicly traded higher education companies wrapped up reporting their quarterly earnings last week, offering a look into the trends affecting them — as well as the larger college and university ecosystem.

Several major developments surfaced, including the ways ChatGPT and artificial intelligence are changing how instructors build courses and students access information. Meanwhile, some ed tech companies are dealing with potential regulatory changes that could seriously harm their business models.

Below, we highlight three trends that higher education companies confronted during the first quarter of 2023.

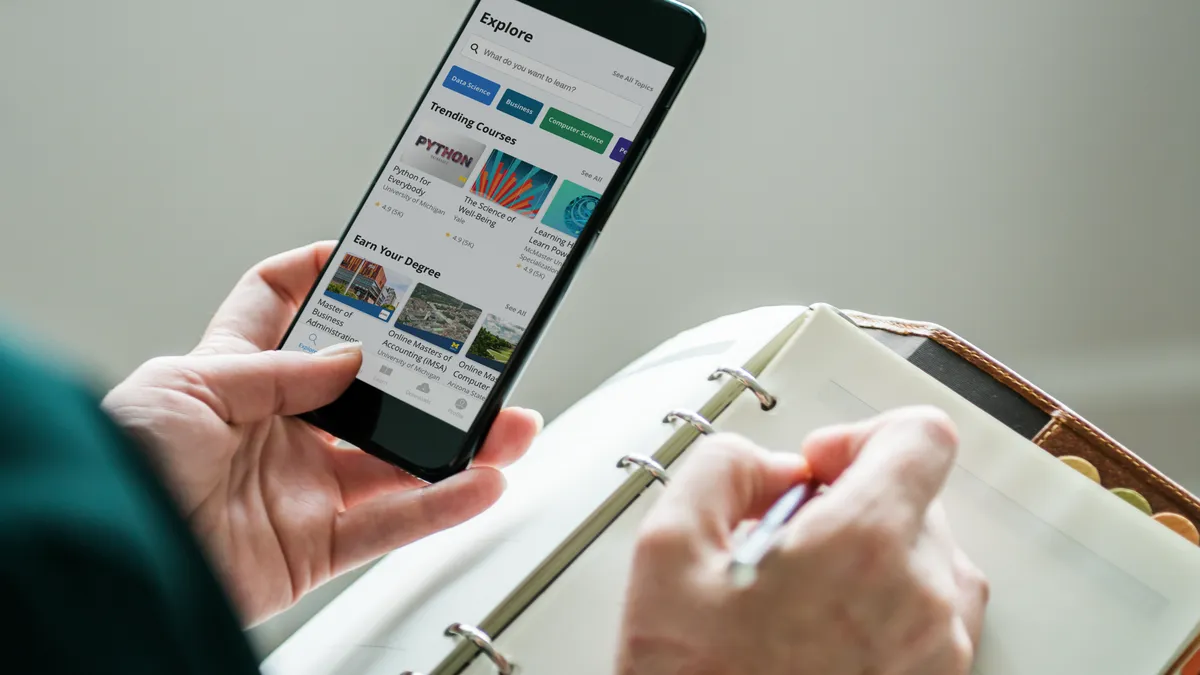

MOOC platforms embrace AI

Although Chegg’s stock made headlines for crashing after the company said ChatGPT was hurting its ability to attract students to the platform, other ed tech companies are heralding the technology as a future driver of growth.

That includes companies that run MOOC platforms. Executives at Coursera, which counts around 124 million registered users, suggested that the company will benefit from workers seeking out training programs as AI takes over more job functions.

“AI will amplify and accelerate the change being felt by individuals, pushing every one of us in every job to keep learning in order to stay relevant,” CEO Jeff Maggioncalda told analysts last month during a call to discuss the company’s earnings.

Coursera is also using AI to enhance its offerings.

The company announced one example in April — a service called Coursera Coach. The service, which Coursera said would be piloted in the coming months, will use generative AI to give personalized answers to user questions. It also will summarize video lectures and point users to clips, helping them understand concepts. Later this year, the company is planning to test using AI to help instructors automatically assemble course content, including by recommending readings and assignments, according to the April announcement.

Other MOOC platforms are developing similar services.

2U, which owns the edX platform, plans to use AI to answer user questions about courses and create summaries of video lectures. And Greg Brown, CEO of Udemy, said the company doesn’t view AI as a threat, but as part of a “massive opportunity for our business.”

“AI is going to, without question, affect top line, is going to affect productivity of our instructors and affect our ability to deliver a higher quality experience in market,” Brown said in an earnings call this month.

OPMs defend tuition-sharing

Online program management companies, or OPMs, have stepped up the defense of their sector. Many of these companies help colleges launch and run online programs, including through enrollment and recruitment services, in exchange for a cut of tuition revenue.

But tuition-sharing has caught the attention of several high-profile Democratic lawmakers, who worry it can lead to aggressive recruiting practices.

The Education Department is currently reviewing decade-old guidance that allows colleges to enter into tuition-sharing deals with OPMs that bundle recruiting with other services. As part of that review, the agency held a listening session earlier this year and asked for public comments about the guidance’s impact.

This news has shaken the industry, as changes to the guidance could crumble the foundation of many OPMs’ business models.

Opponents of the guidance say it’s not consistent with federal law, which bans incentive compensation for recruiting services. OPMs, meanwhile, say tuition-sharing puts them on the hook financially for the success of online programs.

2U is one of the most prominent OPMs in higher education. Its CEO, Chip Paucek, defended tuition-sharing when discussing the company’s first-quarter 2023 earnings last month, telling analysts that “the model works.”

“If we bring in a student and that student drops out, semester one, that’s a disaster for 2U financially,” Paucek said, adding that the company only does well if the student succeeds.

However, one of 2U’s oldest clients, the University of Southern California, has faced accusations that students enrolled in its online social work master’s program graduated with enormous debt loads that they couldn’t afford. The university developed the program with 2U.

Grand Canyon Education, another OPM, also offered a defense of the industry. GCE’s largest client is Grand Canyon University, which split off from the company in 2018. The university now pays about 60% of its tuition and fee revenue to GCE in return for services like counseling and marketing.

Brian Mueller, who serves as both the CEO of GCE and the president of Grand Canyon University, said the company’s business model helps the colleges it works with withstand periods of high inflation or wavering demand for higher education.

“Our expertise, technologies and processes have allowed our university partners to continue to benefit during these challenging times,” Mueller said during a call earlier this month with analysts.

For-profit enrollment is mixed

Several publicly traded higher education companies operate for-profit colleges, offering a peek into how that sector is faring. So far this year, their enrollment has been mixed.

Grand Canyon University, which the Education Department considers a for-profit college for federal financial aid purposes, saw its online enrollment increase to above 86,000 students by the end of March, reversing declines seen last year. The private Christian institution now has about 108,600 students, which is also due to enrollment growth among in-person students.

Perdoceo Education also saw gains, with total enrollment growing 0.8% year over year to around 37,900 students.

Enrollment at Colorado Technical University, its largest institution, was flat at 23,500 students. But American InterContinental University System had 14,400 students by the end of March, up 2.1% compared to the same period last year.

Meanwhile, American Public Education’s Rasmussen University suffered heavy declines, with enrollment falling 12% to 14,300 students.

The company’s executives attribute some of those declines to Rasmussen lacking a permanent leader for the past year. However, the company touted recent news that it filled the role with Paula Singer, who previously helmed Walden University, another large for-profit college.

Walden, which is owned by Adtalem, also saw its enrollment fall. The online college has experienced year-over-year enrollment declines every quarter since Adtalem acquired it in 2021.

The company told analysts this month that it started a new campaign in April to highlight the university's “unique value proposition.”