Imagine this: A student wakes up for her 8:00 a.m. class, but not in time to make breakfast or swing through the dining hall. Before she rolls out of bed, she uses her smartphone to place an order for coffee and a breakfast sandwich at a cafe on campus.

While she's walking to class, her food is being prepared, stored safely inside a robot — essentially a cooler with wheels and autonomous driving capabilities — and sent to her destination.

When she arrives, the robot is waiting outside the building. She unlocks the device using a mobile app and a code unique to her order, removes her hot food and proceeds to class right on time.

It may seem like a scene from a movie — a 21st-century take on the idea of ordering a pizza to class. But for students at George Mason University, in Fairfax, Virginia, it's just another day. And the option is likely to be open to more students as colleges embrace food delivery and mobile ordering on campus.

"Ten years ago, students were digital natives," Ryan Tuohy, senior vice president of business development at Starship Technologies, told Education Dive in an interview. "The students in college today are on-demand natives." The San Francisco-based company makes the delivery robots, and it is deploying them at George Mason in partnership with the university's foodservice provider, Sodexo.

Given the popularity of same-day package delivery, food-ordering apps and other on-demand services, college students are becoming accustomed to getting what they want, when they want it and on their terms. It's a trend evident across the foodservice sector, with general use of digital and mobile ordering continuing to grow.

Sixty-percent of the roughly 6,200 on-campus students at George Mason have ordered food from off-campus restaurants, said Mark Kraner, the university's executive director of campus retail operations. "There's a strong demand for delivery," he said, adding that students typically spend between $250 and $350 a semester on food bought outside their meal plans.

Colleges and foodservice providers are responding to that behavior. Beyond food-delivery bots, they are adding online and mobile ordering at campus dining locations, bringing food trucks to school events, providing 24/7 food service and even offering meal kits as part of their dining plans.

Aramark, for example, recently acquired the on-demand food-delivery service Good Uncle, which provides meals students can purchase through an app and have delivered to designated pickup points on campus.

Ordering on-the-go

Mobile ordering is gaining traction on campuses. Last fall, online ordering and delivery service Grubhub bought campus food-ordering platform Tapingo. At the time, Tapingo was working with more than 150 colleges and integrated with meal plans and campus restaurants.

Students bring the same expectations to campus dining that they have for any other dining experience, Ted Faulkner, Virginia Tech's director of dining services, told Education Dive in an email. This has inspired the university to enhance its service. In 2017, it rolled out its online ordering system.

The ability to order food online and pick it up at a cafeteria sounds simple, but implementing it was difficult, Faulkner said. The university of nearly 35,000 students — some 9,300 of whom live on-campus — had to limit the number of online orders it would process to ensure in-person customers weren't left waiting too long. It also had to create space to prepare the online orders and a designated spot where students could quickly pick them up, he said.

Virginia Tech, which this year was ranked among the top U.S. colleges based on dining by Niche.com, runs its foodservice operation without a partner, Faulkner said.

Use of the system exceeded officials' projections, with 9% of the school's nearly 7 million meals per academic year ordered online. Some of those orders were even coming from students inside the cafeteria who wanted to avoid having to stand in line.

Students pay an extra 49 cents for every online order, a small fee compared to the $1 to $10 typically charged for orders placed through mainstream food delivery services.

The university also runs two food trucks that can serve students all over campus. The trucks handle less than 1% of the university's annual dining output, but along with the online ordering they offer "the immediacy students desire and want," said Frank Shushok, Virginia Tech's senior associate vice president for student affairs, in an interview with Education Dive.

Bringing on the 'bots

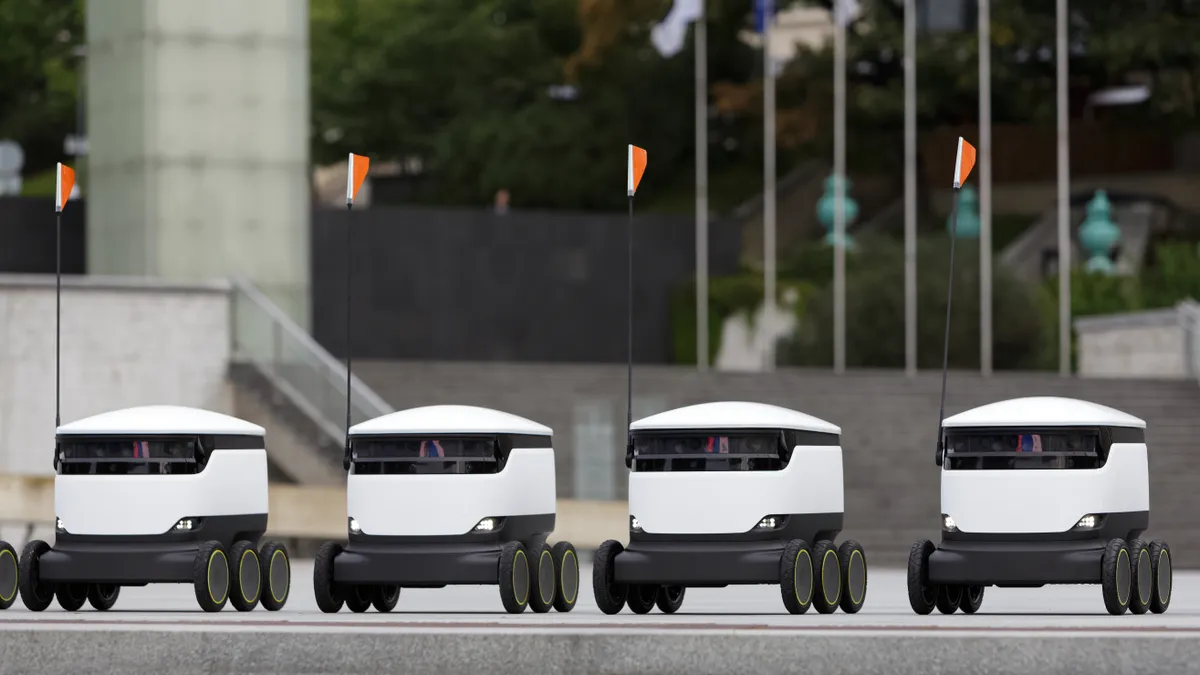

At George Mason, the delivery robots are the stars. (They were popular photo partners during graduation weekend, Kraner said.) Each one has a camera, infrared and radar to help it navigate the nearly 700-acre Fairfax campus. Customers use an app to place their orders and then track and access the deliveries. They can pay for their orders with either dining hall dollars or by credit card.

Users unlock the device with a code delivered through their phones. Each order takes 45 minutes, including 30 minutes of delivery time. Kraner said he hopes to shorten the entire process to 30 minutes.

The university started using robots in January of this year. The fleet of 43 units averages about 350 deliveries a day, Kraner said. The service includes seven on-campus restaurants, such as Dunkin', Blaze Pizza and Starbucks, though it doesn't include dining halls. The robots recently expanded service from 8 a.m. to 2 a.m.

"Ten years ago, students were digital natives. The students in college today are on-demand natives."

Ryan Tuohy

Senior vice president of business development, Starship Technologies

While the service hasn't affected the number of meals served at the university's dining halls, it has led to an 8% to 10% increase in revenue at the participating restaurants, Kraner said. The school shares in the additional revenue generated, he added, but he wasn't able to specify how much. Each order carries a $1.99 fee.

The service's appeal extends beyond students who live on campus. Staff order food on their way into work, and some neighbors unaffiliated with the university have even used the service, Kraner said. (These customers must come to campus to collect their orders.)

The average user places more than one order per week, Starship's Tuohy said, and both he and the university were surprised to see such a strong demand for breakfast orders. "It's becoming part of people's routine," he added.

One unexpected benefit of online ordering, Kraner said, is that it has helped alleviate the rush of students who would typically pour out of class and into a campus dining spot. Some students even time their orders to be ready when class is over.

More campuses add robots

Starship hopes to bring its robots to 100 campuses in the next two years. Other schools to roll out Starship's delivery bots so far include the Northern Arizona and Purdue universities. And starting this month, students and employees at the University of Wisconsin-Madison can order food for delivery from a fleet of 30 bots. The 936-acre campus is so far the largest U.S. university to implement Starship's robots.

Still, a recent implementation at the University of Pittsburgh has run into problems over concerns about the bots' impact on accessibility. And at George Mason, construction activity and bad weather have at times hampered service.

Colleges and foodservice providers must address these and other issues when bringing on-demand services such as delivery vehicles to campuses that are often small cities unto themselves.

Still, officials see promise in the new delivery mode.

"Our students are juggling more than they ever have before, and we are always looking for inventive ways to support their campus dining needs," Peter Testory, director of dining and culinary services for UW-Madison's housing division, said in a statement.