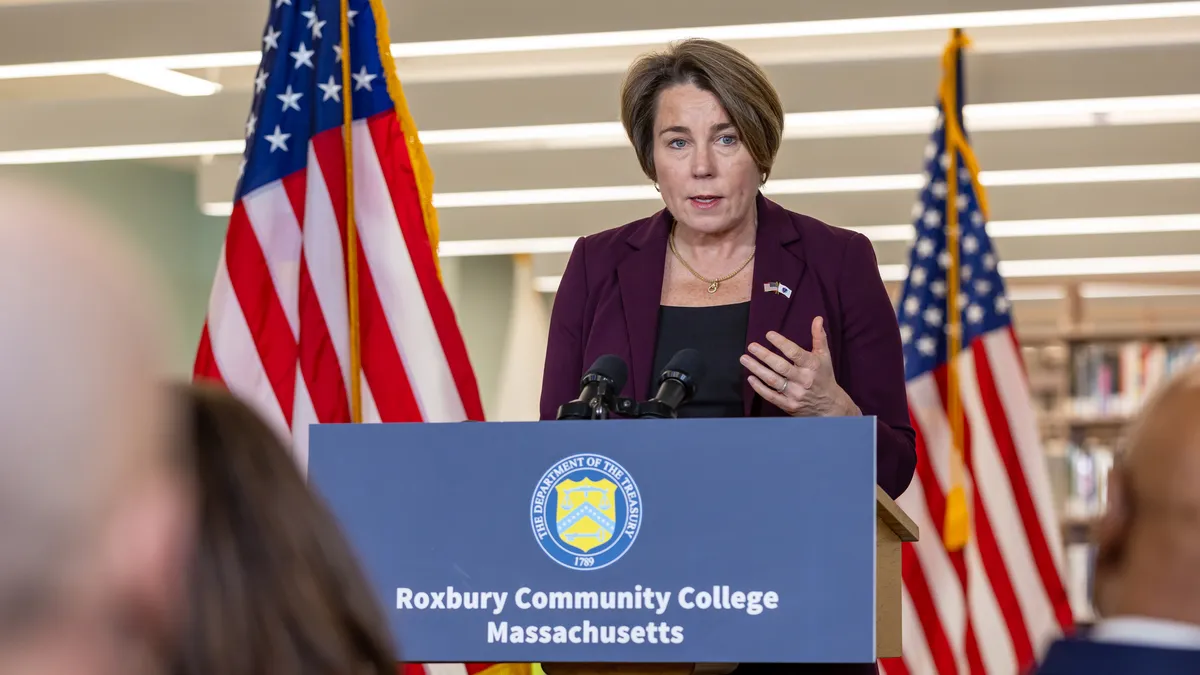

A network of predominantly Black community colleges and historically Black community colleges is in the midst of a two-year effort to find and share best practices so that its members can boost student outcomes.

Leaders suspect institutions across higher ed will have something to learn from the work.

Made up of 22 institutions spanning eight states, the PBCC-HBCC Network is funded with $1.5 million from the Lumina Foundation and the Annie E. Casey Foundation. It's working with a nonprofit group focused on postsecondary attainment, Complete College America, to help identify the support services students need and the courses and competencies employers require.

To meet the definition of a PBCC, an institution must enroll at least 40% Black students, and at least half of its students must come from under-resourced households or be first-generation students. They must also be more affordable than comparable institutions for full-time undergraduates. HBCCs have a historical mission of serving Black students dating back to before the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Two executives at Complete College America, or CCA, spoke with Higher Ed Dive about the network. Yolanda Watson Spiva is CCA's president. Nia Haydel is its vice president for alliance engagement and institutional transformation.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

HIGHER ED DIVE: How did this effort come together?

YOLANDA WATSON SPIVA: CCA started out with four-year public institutions as sort of the highest leverage points. If we could get them completing at a higher clip, then we figured the high tide would lift all boats.

We realized a lot of institutions got left behind with that sort of thinking. CCA did add community colleges, but historically Black community colleges, predominantly Black community colleges, were sort of untouched in this space.

This was really an effort to reclaim where we think we could have had more of an acceleration of the completion effort, and then to basically let them know, "You are a member of the CCA alliance," and then to actually engage them in a way that's significant.

The goal was to convene these institutions that many folks didn't even know existed or that they were classified this way, as PBCCs or HBCCs — then also to try to get in common cause with them around creating a collective impact strategy, and then creating a learning community whereby they could learn from one another but we could also extrapolate those learnings across the wider CCA network.

NIA HAYDEL: One of the reasons this sector is really important is because such a small group of institutions — between 49 and 52, depending on who is doing the counting — account for the education of 10% of all Black students enrolled in two-year institutions. So you have a very small number of institutions doing an enormous amount of work and outreach with this population, yet they are largely unknown.

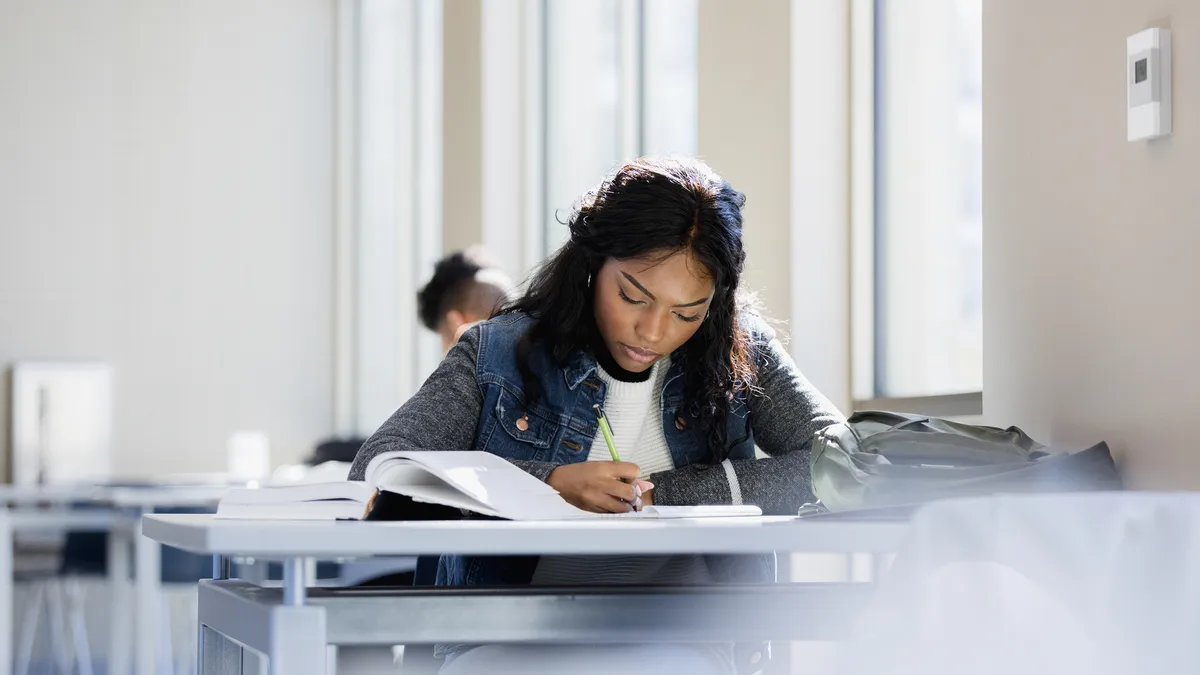

What should we know about the students these colleges serve?

WATSON SPIVA: There's a high concentration of Black students of all backgrounds and ages and socioeconomic levels. Many of them are adults attempting to skill up and enter the workforce, and some are traditional aged.

These students tend to not only have their own basic needs but also tend to be part of a sandwich generation. They are raising children sometimes. They are also taking care of parents or aunts. They have multiple generations of families living in one home, and so their issues are compounded compared to the typical college student.

Looking forward, do you expect to focus on certain types of best practices?

HAYDEL: We're looking at how do we provide wraparound services and basic needs support for students across the spectrum, whether it's day care, child care services, or flexible schedules.

The other thing is really focusing on the pathways from the academic program to credentials of value to the degree. Recognize that we need to have steps along the way in case the students have to stop out, because there is a practical reality for most of the students who are attending.

Through the conversations so far, we realized that a number of these institutions already have stackable credentials. We're looking at how they accomplish that. And we're also working with them to connect with the local workforce to see if the degrees they are offering, the certificates they are offering, really match what the community needs.

Will you be sharing findings outside of the network?

HAYDEL: Some institutions have a very traditional type of population. But that's become less and less the standard, and so I think more and more people will be able to see opportunities in their own institutions in the things that we're learning from this PBCC-HBCC project.

We will have webinars. We will have a report that goes out.

Our position is not to say, "This is the plan and this is the only way you can do it." It really is, "These are the things that we have learned. These are the considerations you should make. If you are in a different situation, maybe these are some of the things you might have to adjust."

WATSON SPIVA: I'd like to also add that our goal with this is to frame these institutions from an asset-based frame and not just from a deficit frame. Because they have been under-resourced, a lot of times that is the only narrative, and we certainly want that information out there. But we also want to highlight the innovation that's taking place on these campuses.

What is the timeline going forward?

HAYDEL: The project actually ends in June of 2023, so by next summer we will have outcomes. Along the way, we'll be able to see partnerships happening, conference presentations occurring and more coming from the group.

WATSON SPIVA: Although we have a finite amount of dollars, our goal during the next 12 months or so is to make sure that we are helping to partner with them for regional funds to help continue the work.

Did we miss anything?

WATSON SPIVA: Just like in the South, where churches are sort of the foundational bedrock, in a lot of these communities, these institutions are really the place where a lot happens beyond just learning for the individual.

Their kids go to summer camp there. The elderly come there to learn computer classes. They are a trusted part of the community.

Our view is that working with these institutions is not going to just direct the learners who are degree seeking or seeking a credential, but also the rest of the community.

HAYDEL: One other thing I would add is that there is a policy component to this project. We talked a lot about practice, but we're also looking at the various policies that will influence how all of these things come to pass at the institution level, the state level and also the federal level.

And then we have an incubator program which we will be launching soon around identifying the next set of executives who want to lead in the HBCC-PBCC space.

People can and should aspire to leadership here. It doesn't have to be in the four-year space to be successful, and I think that's really important for everybody to understand.