On the list of areas in need of improvement in higher ed, few would dispute including the bridge from college to career. More funding, better training and heightened awareness across campus of the kinds of services available to students have all been cited as ways of bettering the process.

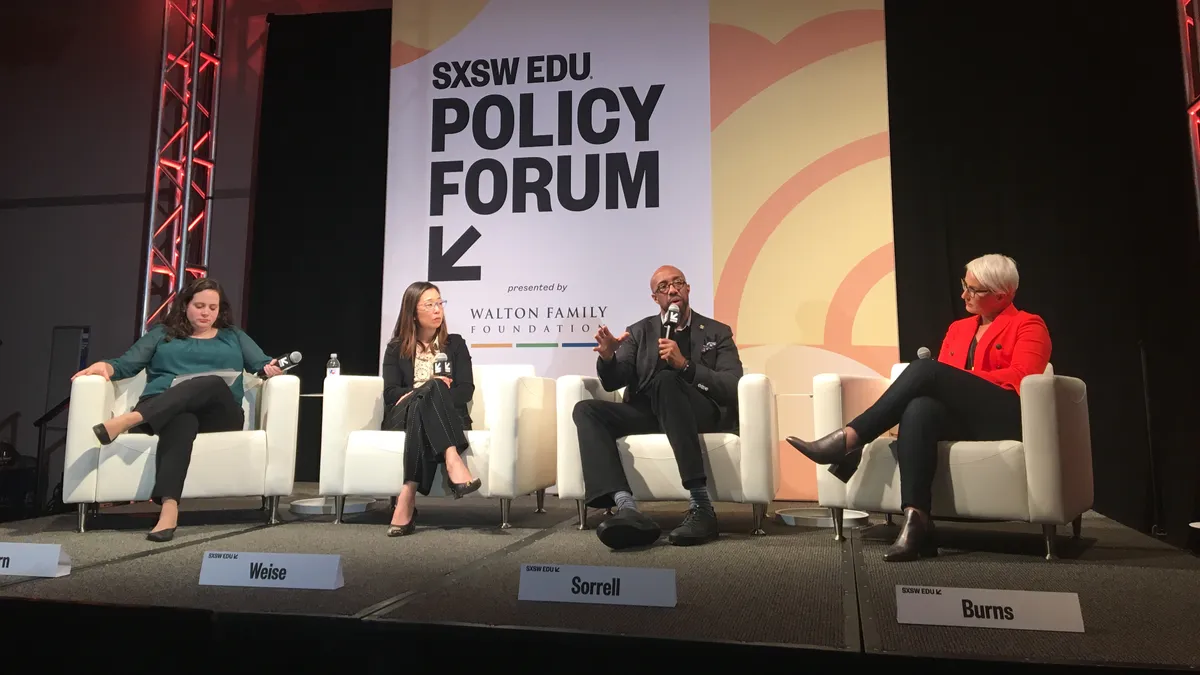

And they were a point of discussion among higher ed leaders on Monday at the ninth-annual SXSW EDU, in Austin, Texas — particularly for underserved student groups.

"We think that by bolting on a career services office, disrespecting it, underfunding it, not taking it seriously, shoving it in a basement somewhere, that students are going to somehow, like through osmosis, get everything we wish they would to prepare themselves," said Bridget Burns, executive director of the University Innovation Alliance, during one panel on the topic.

"We need to intentionally design a handoff so we are integrating the curriculum experience and what will prepare (students) for the workforce and it's a seamless transition," she added.

Just one in three college students thinks what they're learning in school will help them find success in the job market and the workplace, according to data from Gallup and the Strada Education Network. Other research shows students are more likely to get career advice from their instructors than from career services.

Yet, according to a separate Strada report, four in 10 graduates were underemployed in their first job after college. Five years later, two-thirds were still in that position.

Colleges are moving to change that. As one recent example, seven UIA members, all large public institutions, are teaming up to share best practices for improving career services for low-income and first-generation students.

Models for the future

Small institutions can provide replicable models for these groups, too.

Michael Sorrell, president of Paul Quinn College, in Dallas, offered one example. Under Sorrell's leadership, Paul Quinn turned from a struggling liberal arts college nearing closure to a federally designated urban work college. Now, it is on the upswing and expanding its model to other institutions.

"If you come to Paul Quinn College, you get a job," he said, referring to a key element of its curriculum through which students work on- or off-campus between 10 and 20 hours a week in exchange for a $5,000 tuition grant. In class, students learn soft skills such as writing, public speaking, group projects and digital skills. Most Paul Quinn students qualify for Pell Grants and have zero expected family contributions to their tuition.

His students' socioeconomic position is driving his focus on ensuring they have real-world work experience.

"By the time you graduate from Paul Quinn, you have an academic transcript, you have a work transcript and then you have four to eight digital certificates," he said. "We think we have poverty-proofed higher education."

He adds: "This is not a middle-class conversation. We are speaking to people who haven't been spoken to."

But the focus on work experience is a salient one across higher ed today. A separate Gallup report revealed that graduates were more likely to immediately find good employment if they had a job or internship that gave them hands-on experience with what they're learning in the classroom.

Focusing on post-graduate employment — a growing imperative as colleges address the demand for a more clear-cut return on investment as tuition rises — has been cause for concern in some corners of higher ed. And panelists, including Sorrell, cautioned against declining investment in the liberal arts.

"We are looking for nimble people who are able to exercise judgment in the most ambiguous of circumstances," which are skills commonly attributed to a liberal arts curriculum, explained Michelle Weise, chief innovation officer at the Strada Institute for the Future of Work.

She added that higher ed's silos are getting in the way of helping students understand how what they're learning in one class can transfer across disciplines.

Whose job is it?

Bringing faculty members and employers into the career readiness discussion can help the two sides work together on improving the handoff, panelists said.

UIA, Burns said, is planning to launch an employer working group to take on issues such as redesigning the internship process to accommodate students with greater financial need or determining what skills and proficiencies graduates are lacking.

"In the end, we are not producing workers," Burns said. "We are producing master learners who are capable and nimble to adapt to the workforce." She emphasized, though, that colleges and employers need to be "equal partners" in this process.

Weise noted the emergence in the last few years of the broader marketplace linking education and employment — which she said is worth more than $2.9 billion and includes 250-plus companies funded to address the issue. They cover topics that include teaching low-income, first-generation students how to use social capital to get a job (and that it's OK to do so), and designing apprenticeships for new tech skills.

"We need to intentionally design a handoff so we are integrating the curriculum experience and what will prepare (students) for the workforce and it's a seamless transition."

Bridget Burns

Executive director, University Innovation Alliance

To gather better data on graduate outcomes, colleges should stay in touch with alumni beyond soliciting donations or hosting events. A stronger connection between career services and the alumni office is one place to start, Burns suggested.

According to the Strada-Gallup Alumni Survey, just one in 10 graduates found their undergraduate alumni networks helpful in their career so far, though graduates of higher-ranked schools reported higher satisfaction. One reason for the low opinion, researchers suggested, may have been that colleges oversold the value their alumni networks could provide.

Yet keeping in touch with graduates is important, as it can help colleges identify the points at which they hit a higher-earning career track and what the stumbling blocks were leading up to that, Weise added.

As demand for new skills pushes students toward lifelong learning, maintaining those relationships will be important.

"We are going to have to come back to learning in some sort of way, and it's probably not going to be with our universities," Weise said. "If we are fumbling it right now, why would I return as a 55-year-old male who is finding his skills are waning? Why would I go back to the school that made it so difficult for me in the first place?"