As colleges' purse strings continue to tighten, a world of digital transformation is opening up before them. The extent to which they participate, however, depends on how that change can help lower costs and improve student outcomes.

"At first, as an educator, I said, 'Oh, that's terrible,'" said Paul Friga, special advisor to the provost for online education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, of the funding cuts. "But it might be necessary to get universities to make change."

It's not the only catalyst. Incoming college students are more tech-savvy and willing to engage digitally than prior generations, said Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education. That's increasingly the case among administrators, too.

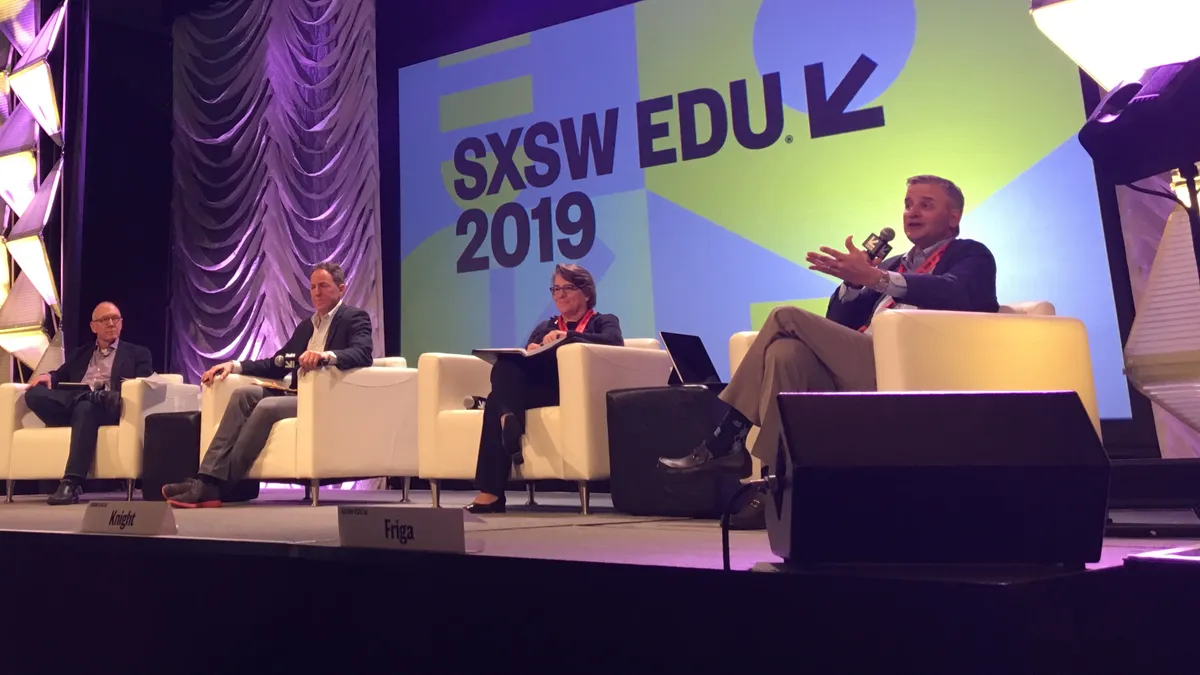

The potential for digitally driven change was up for debate at this year's SXSW EDU, held this week in Austin, Texas, where Friga and others representing industry groups, colleges and online learning providers discussed how technology can help higher ed solve some of its biggest problems — and where it alone won't be enough.

Improving student outcomes

When the University of Texas at Austin wanted to improve graduation rates, it looked to predictive analytics to help figure out what was making some students more successful than others.

"It turns out, having a job on campus made a big difference in graduation rates," said Mary Knight, special assistant to the senior vice president and chief financial officer at UT Austin. "Being from the administrative area, we don't interact with students on a daily basis, but that was something we could help with. We can give students a job."

UT Austin had a goal of increasing its four-year graduation rate from 52% in 2012 to 70%. Last year, it nearly reached that goal with a rate of 69.8%. New approaches to analyzing student data, such as predictive analytics, was key to that improvement, according to the university.

The kind of technology-based intervention Knight described also has implications for operations, Friga said. "(That) provides a way to increase her capacity and also lower costs because by keeping the student in place, you have less of a replacement cost and you (don't) have to start over," he said.

Friga is also co-founder and chief strategy officer of the Academic Benchmarking Consortium. The group of 30 some institutions shares administrative labor data and advises on how they're spending across campus. Among the factors they've looked into is the relationship between student services spending and retention, graduation and post-graduate income.

Career services, they learned, was the area of student services that had the biggest impact on those outcomes. That can guide spending decisions. "In a period of limited resources, where do you invest when you do have the money and if you are able to free something up, where should you invest more?" he asked. "And there's a lot of pressure on universities to think about outcomes more than we have before."

The digital transformation underway has connections to equity "in the way in which information can flow to groups of students who typically don't have informal access to it," Mitchell said. He offered a few examples: developing 311-style systems, implementing digital alerts such as nudges for financial aid applications, and, like UT Austin did, using predictive analytics to identify and support at-risk students.

Managing costs

Efficiency has a catch, Friga says: "That means people have to be let go, and that doesn't usually go over very well at a university." Rather than make corporate-style personnel cuts, institutions tend to phase out positions by not filling them when they become open. "So it takes four to six times as long to get efficiencies (as) you would get in private industry."

Mitchell offered a different perspective: "Could you also think about efficiency as getting a better and higher volume of product with the investment we are making?"

In today's environment of consolidation across higher ed, they can find efficiencies that don't necessarily have to do with cost-cutting, said John Katzman, founder of online program manager Noodle Partners and, previously, 2U. "Any school giving an online program has sort of infinite capacity there," he said.

Friga agreed that broadening an institution's offerings, such as by expanding online, can provide a bigger base over which to spread costs. But growth has limits, and the online space is currently homing in on a particular group of students: nontraditional learners.

Especially in digital, there is a close correlation between efficiency and capacity, Mitchell said, though in online there is a hefty upfront cost to consider.

In response to budgetary pressures, colleges and in particular state systems are looking to scale online while they seek to lower student costs by reducing or eliminating tuition increases.

A strategic approach

Successful digital transformation is about strategy as much as technology, the panelists agreed. "You reinvent the process and then you can bring in a technology as an enabler to make it stick," Friga said.

To help, the panelists recommended pitching faculty on the time-saving elements of the digital change in order to get their buy-in. Communication is also important to ensure stakeholders across campus have the opportunity to be involved.

While that communication and training can be costly, it is critical, Knight said. She cited a recent ERP implementation on her campus for which the institution "really invested in the culture change, the training, getting faculty involved," she said. "There's always bumps along the way, but I think everyone realized that."

To manage cost and maintain control of the project, institutions working with consultants should focus their involvement on specific functions, such as project management, scope-setting and sharing expertise from past projects. "They could be a good catalyst to get things going," Friga said.

Counter-pressures ahead

When asked what higher ed will look like in 20 years, the panelists said they expected most of the change to happen with behind-the-scenes differences in pedagogy and operations.

Campuses will have more interdisciplinary curriculum and hands-on learning opportunities, Knight said, adding that she hopes relationship-building and collaboration will remain part of the higher ed experience.

Friga expects relatively little change to institutions' core offerings. The bigger shift, he said, will be in the relationship between institutions and students to a lifelong learning model that mixes online and on-campus instruction. Certificates and other specialized offerings will increase, too, he predicts.

"It won't be, 'Come here for four years, see you later, give us money as an alum,'" he said. "It will be, 'We've got something for you right now for a year or two. Go do some work. We've got something a couple of years after that. We want to be your lifelong partner, stay with us.'"

Katzman agreed: "There's a tremendous opportunity for higher ed to be right in the middle of our whole lives." He expects online learning will play a key role, with the change focused on post-graduate programs.

"As we talk about the next 10 to 20 years, we need to be very clear that this is not just an open playing field for us. There are counter-pressures we need to be very, very aware of."

Ted Mitchell

President, American Council on Education

Higher ed isn't undergoing this change in a vacuum. In addition to shifting demographics and increasingly sophisticated technological supports, government intervention is also a consideration. Mitchell cites growing attention on performance-based funding by states as one example, as well as the recent threat by President Donald Trump to use executive privileges to cut federal research funding to institutions based on whether they "support free speech."

The current rulemaking hearings on accreditation also indicate how federal oversight can affect pathways for individual institutions and industry competition in higher ed.

"There is an important, increasingly negative narrative about our work," Mitchell said. "That (if) we’re not going to fix our own house — and that's cost, that's price, that's accessibility, that's outcome — (the government) will come in and do it."

He added, "As we talk about the next 10 to 20 years, we need to be very clear that this is not just an open playing field for us. There are counter-pressures we need to be very, very aware of."