Scott Bass is a professor and executive director of the Center for University Excellence at American University, in Washington, D.C., where he served as provost from 2008 to 2018. He is the author of “Administratively Adrift: Overcoming Institutional Barriers for College Student Success.”

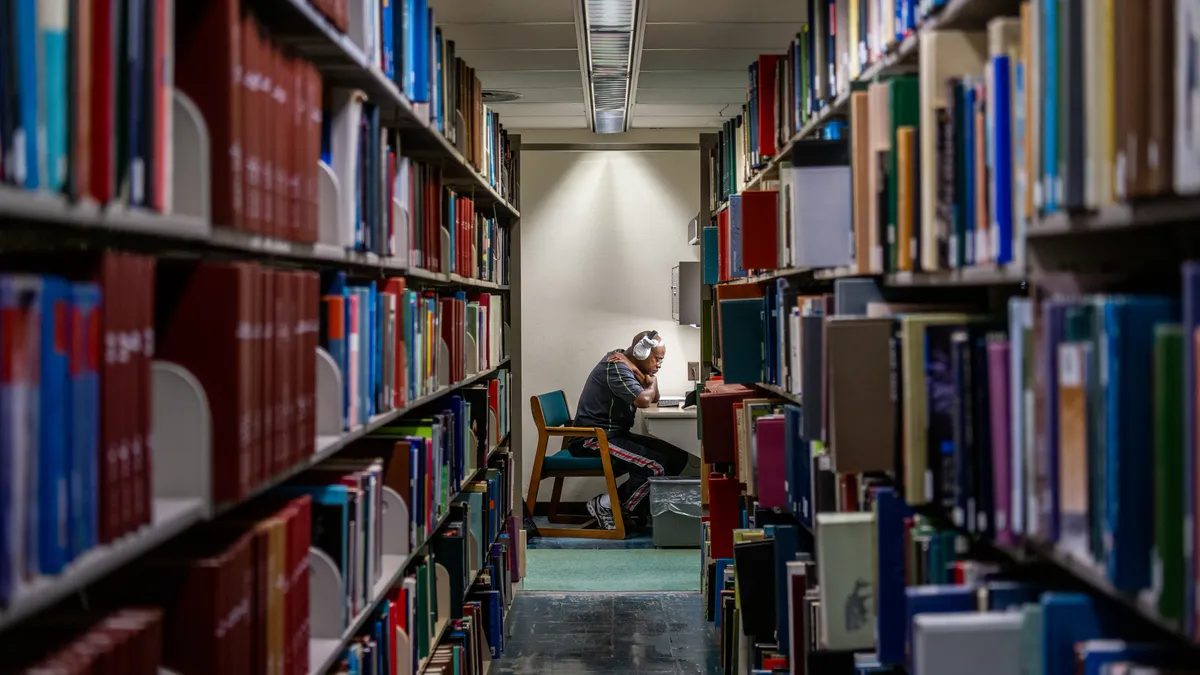

While today’s students face many of the same stressors as their peers in prior decades, what is different today is the psychological weight carried by Generation Z upon entry into college due to a barrage of tragic and unprecedented world events and their reliance on social media. This combination, coupled with expectations cultivated by the increasingly efficient, integrated and personalized digital-service world in which they were raised, makes our job as educators that much more challenging.

That is, students arrive carrying a hefty psychological burden to a campus setting that has struggled to keep pace with the holistic service delivery systems that students are accustomed to. In order to fully promote student mental health, we need to both provide psychological support for those in need and address how we deliver many of our student services.

On most campuses, administrative and support services remain semi-independent offices, just as they were before the pandemic. By design, it is a model limited in its capacity to look holistically at the end-user experience, making it difficult to provide timely support that can be pivotal to a student’s academic success, well-being and mental health.

At American University, we embarked on a multi-year examination of the student experience and found that for too many students, the prevailing service administration can inadvertently add an unnecessary layer of frustration and stress. We sought to improve the individual experience on campus by better delivering existing administrative services and mitigating challenges students might be encountering.

The process, which began in 2015, included student focus groups, workshops, retreats, journaling projects and case studies to better understand the student experience. Faculty and staff came forward with specific difficulties they encountered when trying to solve problems that were engulfing their students. We tried to walk in our student’s shoes.

We found over 60 “pinch points” that inadvertently chafed students, adding stress and anxiety. The students provided us with specific examples that included academic advising and support, financial aid, student affairs, registration and student accounts. The case studies and other evidence confirmed services were not aligned across the board.

We identified communication problems, lost records, delayed or contradictory responses, misinformation, counterintuitive policies, inefficient practices, inattentiveness and examples of students trapped in sticky bureaucratic webs. Even some of our most successful students expressed frustration in routinely dealing with a potpourri of uncoordinated, time-consuming administrative functions. Where we could, we sought to make improvements.

The following suggestions reflect what we learned about improving service delivery to students. They applied to American University, and they will likely be useful elsewhere:

- Gather data about the student experience from the students themselves. Listen to their stories and encounters with different offices. The labels they attach to the offices can be telling, like the “Bermuda Triangle” where documents go never to be found, or the “hidden curriculum” referring to terms and procedures well known only to insiders. Embedded in these reports are clues for organizational changes that can help reduce frustration and stress.

- Involve professional staff in identifying stressors and pinch points. One suggestion is to host a lunch for a group of direct service administrators. The ticket for attendance is that they bring at least two difficult student cases that they worked with. It will give insight into how difficult it is to solve the challenges they encounter and provide ammunition to resolve thorny internal problems that can derail students and vex staff.

- For the newest students, examine the flow of information from different offices before they arrive on campus. At American University, several years ago, we learned that we sent an uncoordinated barrage of information after the student’s initial deposit but before arriving on campus, totaling 130 messages from different offices. For students, this signals the culture of the setting and, given the volume, raises issues of prioritization.

- Examine the way four key service clusters are offered to students. Are the four corners of life on campus — academics, social life, health (including mental health), and financial needs — integrated, with a professional advising the student with timely information? More integrated approaches have been promoted by Achieving the Dream, involving over 300 community colleges. They report success in breaking down administrative silos and fostering a student-centered approach. The Pullias Promoting At-Promise Student Success effort has tested recommendations designed for a more holistic approach to student success and well-being. Numerous historically Black colleges and universities, colleges for women, and liberal arts colleges are valuable resources with long traditions of student-centeredness and cultivating a sense of belonging. Another approach for helping students navigate multiple specialists, commonplace outside of higher education, is the establishment of a case-management system.

- Ensure leadership prioritizes a student-centered healthy environment throughout the organization. One idea used in the private sector is the creation of a chief experience officer, or CXO, reporting to the campus president. CXO responsibilities include fostering programs and initiatives that are designed to prioritize student success and well-being by all units. Some campuses have engaged the president’s chief of staff as a point person to ensure all offices, whether providing direct services or not, are focused on the quality of the student experience.

While there is no quick fix or prescriptive solution for the traumas students bring to campus, there are many ways to better manage their stress and anxiety. The reality is that creating a healthy environment on campus involves everyone and includes how we provide student services.

We must rethink the way the campus delivers its services to students so that it is more empathetic, integrated, customized, timely and personal — an experience comparable to what they encounter elsewhere — or we risk sidestepping a necessary response to a stressed student body.