Dive Brief:

- The federal government's systems that allow student borrowers to repay loans based on their income are flawed and can end up saddling them with more debt, a new report argues. This can affect borrowers' financial health and well-being, it says.

- While debt under these income-driven repayment plans can theoretically be forgiven after 20 to 25 years, it seldom is, according to the research, published by the Student Borrower Protection Center, a Washington D.C.-based advocacy organization.

- It calls on the U.S. Department of Education to stop adding unpaid interest to the principal of these loans, among other changes to the model.

Dive Insight:

The first income-driven plan was introduced in the 1990s as a more affordable path for student borrowing. Today, the plans align loan payments with how much a borrower earns, and some of those with the lowest incomes have a $0 monthly payment.

Policymakers over time have tweaked repayment terms and the forgiveness timeline of these plans. But the new report, written by Mark Huelsman, a senior fellow at both the SBPC and the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice at Temple University, suggests they can disadvantage borrowers, especially those in the lowest income brackets.

That's because those who qualify for low monthly payments "often face the frustrating experience" of their loan balances growing because the payments do not cover interest, the report states.

Worse, unpaid interest is sometimes capitalized, or added to the loan principal, accumulating even more interest.

"These structural failures are by design: IDR was built to be a debt trap," the report states.

While some borrowers have their interest subsidized, they still must navigate the "notoriously complex" repayment system, according to the report, and loan servicers do not always help borrowers sign up for and stay enrolled in plans. Nor do they always help borrowers update their income, which is required annually.

The report also notes the wealth gaps between White families and Black and Latino families, saying the pitfalls of income-driven repayment plans could exacerbate these inequities. And low-income students being burdened with more debt impedes their ability to build wealth, the report states.

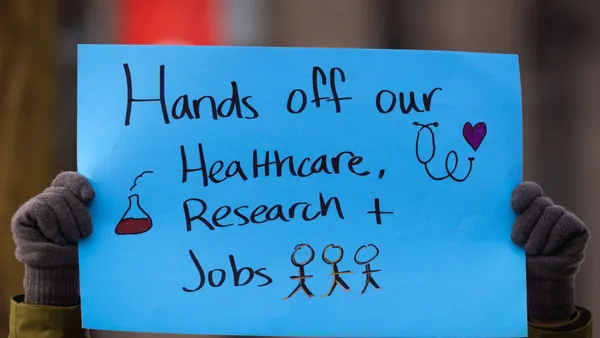

Expenses such as healthcare and housing continue to rise, so "simply owing on student loan debt — and, in particular, doing so for an extended period — makes it all the more difficult for borrowers to grapple with these growing costs," the report says.

While after 20 to 25 years, the balances of these income-driven loans can be forgiven, they typically are not. The report points to a recent analysis by National Consumer Law Center that found only 32 borrowers' loans have been erased in the time that these plans have existed. Two million federal student loan borrowers have been in repayment for 20 years, though this count includes those outside of income-driven plans.

The NCLC blamed the small number on the U.S. Department of Education mismanaging the program and loan servicers not steering borrowers to these plans.

The new report called for the Education Department to fully subsidize unpaid interest for income-driven borrowers. Those who qualify for a $0 monthly payment or who have to pause repayment, "should not see their balances balloon," it said. The department should also stop capitalizing borrowers' interest and should cancel a portion of the debt of those who make low monthly payments for a certain period.

The Biden administration is rewriting regulations concerning student loans and has forgiven millions of dollars worth of student debt.