UPDATE: Feb. 11, 2025: A federal judge late Monday barred the National Institutes of Health from enforcing massive cuts to grant funding for researchers’ indirect costs, a move widely decried by universities and other research institutions.

U.S. District Judge Angel Kelley issued restraining orders in two separate cases filed earlier Monday against NIH, including one by 22 state attorneys general and another by the Association of American Medical Colleges and other groups. A third lawsuit — brought by the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, the American Council on Education and the Association of American Universities — was also filed late Monday.

Regarding the AAMC case, Kelley wrote that plaintiffs would “sustain immediate and irreparable injury” without a restraining order against the NIH funding cap. Along with restraining orders, Kelley required NIH to provide biweekly status reports confirming regular disbursements.

Dive Brief:

- A coalition of 22 attorneys general filed a lawsuit in federal court on Monday seeking to block the National Institutes of Health's newly announced research funding cuts.

- NIH announced Friday it would cut roughly $4 billion a year worth of funding for indirect research costs such as administration and facilities — by capping reimbursement for these expenses at 15% for current and new grants.

- Research institutions have previously negotiated individual indirect cost rates, with an average of 27% to 28%, NIH said. Organizations, universities and researchers quickly raised alarms about the cuts, warning they could hurt important medical research and the economy.

Dive Insight:

NIH framed its unilateral decision to cut indirect costs as bringing them in line with practices at nonprofits such as the Gates Foundation, which caps indirect costs at 10% for higher education institutions, and the Rockefeller Foundation, which sets a 15% ceiling for colleges and universities.

In a Friday memo outlining the new policy, the agency said the new cap would “allow grant recipients a reasonable and realistic recovery of indirect costs while helping NIH ensure that grant funds are, to the maximum extent possible, spent on furthering its mission.”

The same day, the agency flagged on the social media platform X the “old” indirect cost rates negotiated by Harvard University, Yale University and Johns Hopkins University — which are all between 63.7% and 69% — as well as those institutions’ endowments ranging from $13 billion to $53 billion.

NIH noted that of the $35 billion it spent on grants in fiscal 2023 to universities, medical schools and other research institutions, about $26 billion went to direct research and $9 billion went to overhead in the form of indirect costs.

Sen. Patty Murray, a Washington Democrat, described NIH’s move as an illegal violation of an appropriations bill that prohibits modifications to NIH’s indirect cost funding. Murray also said that the move will shift costs onto states rather than reducing them.

In their lawsuit, the attorneys general argued, “Without relief from NIH’s action, these institutions’ cutting-edge work to cure and treat human disease will grind to a halt.”

They pointed to the legislation flagged by Murray that protected indirect reimbursements: During President Donald Trump’s first term, his administration in 2017 included a 10% cap in its budget proposal, but Congress responded the next year with an appropriations provision prohibiting NIH from modifying reimbursement rates, the lawsuit said.

Filed in U.S. District Court in Massachusetts, the 59-page lawsuit — brought overwhelmingly by Democrat-led states — seeks both preliminary and permanent injunctions blocking NIH from enforcing the rate cap.

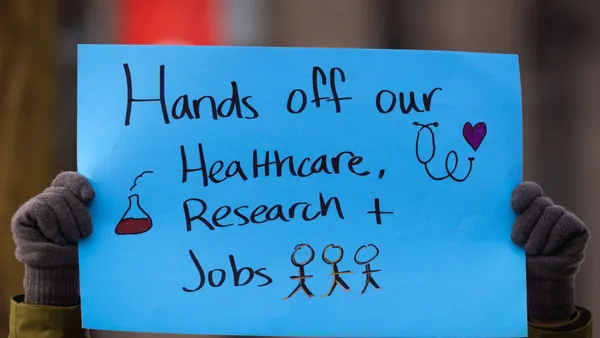

Many in the higher education sector reacted with dismay over NIH’s move.

The decision “sabotages the decades-long partnership that has ensured U.S. global leadership in life-saving medical research,” American Council on Education President Ted Mitchell said in a statement on Friday.

“This decision is short-sighted, naive, and dangerous,” Mitchell added. “It is a self-inflicted wound that, if not reversed, will have dire consequences on U.S. jobs, global competitiveness, and the future growth of a skilled workforce."

Mark Becker, president of the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, described NIH’s policy change as a “direct and massive cut to lifesaving medical research.”

“NIH slashing the reimbursement of research costs will slow and limit medical breakthroughs that cure cancer and address chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease,” Becker said in a statement. APLU noted that funded indirect costs include patient safety, research security and hazardous waste disposal.

Jeremy Day, director of the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Comprehensive Neuroscience Center, said on social media that NIH’s cut would “cripple research infrastructure at hundreds of US institutions, and threatens to end our global superiority in scientific research.”

Meanwhile, institutions are grappling with what it means for their research programs going forward. The University of Michigan, for instance, said in a statement that NIH’s indirect cost funding supports development and maintenance of its laboratories as well as information technology and administrative support for regulatory compliance.

“This change would result in a significant decrease in the amount that U-M receives from the federal government to conduct vital research,” the university said.

Others echoed the warning. In a statement, the University of Wisconsin-Madison said NIH’s directive would “significantly disrupt vital research activity and delay lifesaving discoveries and cures.”

“Indirect costs contribute to everything from utilities charges to building out the laboratories where science is done, to infrastructure for clinical trials of new medicines and treatments,” the university said.