A little less than half of the students at Fort Lewis College, a public liberal arts school tucked away in mountainous rural Colorado, are Native American.

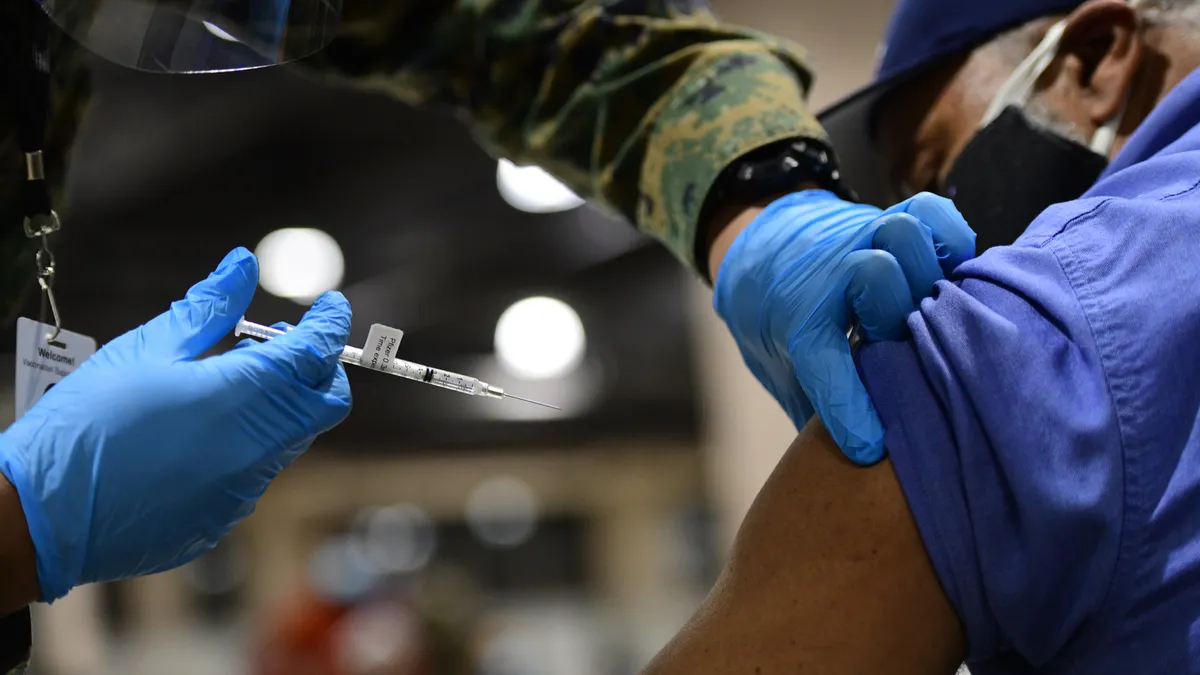

The pandemic has hit this population particularly hard nationwide, which factored into the college's move, a spokesperson said, to become one of the first U.S. higher education institutions to mandate that students receive the coronavirus vaccine in order to participate in on-campus activities this fall.

It's a decision the school weighed heavily. While the U.S. races to immunize its population against the coronavirus, some people are refusing to get vaccinated for several reasons, including that the shots were developed under a speedy timeline. A quarter of U.S. adults said they won't get vaccinated according to polling done in late March, though that share was shrinking in the preceding weeks. A temporary pause in administration of the Johnson & John shot to investigate a rare potential side effect added further complications.

Meanwhile, a partisan debate is raging nationwide about whether employers, businesses and other entities can require people to get the shots.

At Fort Lewis, reactions to the vaccine mandate were decidedly mixed, said the spokesperson, Lindsay Nyquist. However, the college is crafting messaging it hopes will help assuage students' and families' concerns about the requirement, she said. The college enrolled more than 3,200 undergraduates in the fall of 2019, according to federal data.

Other colleges could follow its lead. A fast-growing contingent of public and private schools are requiring the vaccine this fall. They range from prominent research universities including Rutgers and Cornell to small private liberal arts colleges such as Hampshire and Sarah Lawrence.

"When you take a stand on an issue, this is bound to happen," Nyquist said of criticisms of the school's decision. "But we want to communicate really openly with our families."

Higher ed vaccine mandates and the law

Colleges typically require incoming students to be vaccinated against certain diseases, such as measles, mumps and rubella, and are on solid legal ground to do so. A California court late last year upheld the University of California system's mandate for the flu shot, a vaccine more colleges have begun to require.

The coronavirus vaccines being administered in the U.S. add a new twist. They have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration under an Emergency Use Authorization, which gives the agency the ability to make them available more quickly than usual because of the public health crisis.

It's a designation that may make some institutions more hesitant to enforce a requirement, according to legal scholars. Because colleges have never ordered students to receive a vaccine authorized under an EUA, they are entering uncharted legal territory.

The law governing EUAs is also unclear on this, Dorit Reiss, a law professor at UC Hastings College of the Law, said in an email. It requires people receiving an EUA-approved vaccine to be told they can refuse it, but mentions nothing about employers or colleges, which typically have the power to mandate vaccinations. Courts haven't ruled on this yet, Reiss said.

"So universities may be concerned that courts will strike down a mandate under an EUA," Reiss said. The California State University system and the UC system say they will only require the vaccine once the FDA gives one or more of the shots full approval, which would align them with other shots colleges require.

Private colleges are more likely to require them because they aren't governed by the same laws as their public counterparts, said Scott Schneider, a higher ed law specialist and partner in the Austin, Texas, office of Husch Blackwell. He doesn't think litigation challenging mandates would succeed against any college because they already have legal backing to require vaccines.

States have begun to weigh in on the issue.

A recent legal analysis from the Maryland attorney general's office found that the University System of Maryland could legally require the vaccines. The system went on to institute a mandate for the fall. An opinion from Virginia's attorney general came to the same conclusion for the state's public colleges.

Other state leaders, including Gov. Kate Brown, of Oregon, and Gov. Jared Polis, of Colorado, both Democrats, have indicated their support for mandates.

And the American College Health Association said Thursday that it recommends colleges require the vaccine for students and frontline student health workers, if state laws and resources allow. The organization, which also said employees should be strongly advised to get the shot, suggested institutions consult with their legal counsel should the FDA not give full approval soon. But vaccine mandates "are not new and are time-tested," it said.

Chris Marsicano, who runs the College Crisis Initiative, an academic group that tracks institutional responses to the pandemic, expects more schools will enforce the shots but are waiting to announce until either May 1, the traditional deadline for students to commit to institutions that don't offer rolling admissions, or for the FDA to grant the vaccines full approval.

"A lot will happen after students send in those deposits," Marsicano said.

What will vaccine mandates entail?

At Fort Lewis, officials will be sending out "a lot of email communications" about the vaccine policies, and will be hosting several town halls to discuss it, Nyquist said. The school's public health professors will be on hand to answer questions during these events, she said.

Fort Lewis students must either receive their vaccine through the school, or upload an immunization record demonstrating they have received at least one dose. (Two of the three approved vaccines require two shots.)

Duke University, in North Carolina, another school that plans to mandate the shot, will also ask for proof of vaccination. Other institutions may not be so stringent in their mandates. Northeastern University, in Massachusetts, is still debating whether students will need to show documentation of their vaccine or whether officials will take them at their word, The Associated Press reported.

Colleges are letting people opt out of the coronavirus vaccine for medical and religious reasons, just as they do for other vaccinations. Reiss does not expect exemptions to differ for the coronavirus vaccines. Medical exemptions stem from the Americans with Disabilities Act. Religious exemptions aren't legally required, however, so colleges "may choose to treat this vaccine differently" than others they mandate, she said.

At many colleges, students who get an exemption will be regularly screened for the coronavirus. Fort Lewis will ask those students to participate in weekly testing, and to isolate if they test positive for the virus or come in close contact with someone who has. Students who don't comply with the rules will be booted from in-person classes.

Complicating factors for state colleges

Public colleges may face more hurdles when trying to issue a mandate. Some states are blocking public agencies, including those institutions, from mandating the vaccine.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, issued an executive order in early April banning businesses from requiring customers to show a vaccination record. This caused a private institution in the state — Nova Southeastern University — to do away with its vaccine requirement.

A similar executive order came from Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, another Republican, barring public and private entities that get state funds from asking for proof a person received a vaccine approved under an EUA.

And Utah passed a law preventing public colleges from requiring students and employees to get the vaccine.

Because they're an extension of the state, public colleges will have less, not more, freedom to skirt any limitations it imposes, Reiss said.

"A (public) university's ability to resist would depend on the legal framework," she said. "[D]id the state constitution give it any independence?"

If states are forcing colleges to eschew vaccine requirements, then they should pay for the schools to conduct more robust testing for the virus, said Marsicano, who throughout the pandemic has urged colleges to screen students intensively and for students to have priority in vaccine distribution.

Colleges have an increasingly national reach, and Marsicano predicted that some schools in states that block vaccine requirements will lose students to competing institutions in others that do not. "One of the only ways to get back to normal is to vaccinate your way out of it," he said.