Dive Brief:

- Research universities won an extended reprieve Friday when a federal judge permanently barred the National Institutes of Health from capping funding for indirect research costs at a 15% rate, a move that would cost institutions billions a year.

- U.S. District Judge Angel Kelley ruled NIH had violated federal statute, was “arbitrary and capricious” in creating the cap, failed to follow rulemaking procedures when doing so and violated constitutional prohibitions on applying new rules retroactively.

- The permanent injunction came in response to NIH’s request earlier on Friday for a final judgment in the case so as to expedite the appeals process — meaning the litigation is very likely to continue.

Dive Insight:

Kelley’s permanent injunction on Friday extends a preliminary injunction she issued in early March. In its Friday motion, NIH signaled that it planned to appeal the case in the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, setting up more legal battles ahead.

Still, those who are fighting NIH’s indirect funding cap applauded Friday's ruling. If nothing else, it buys institutions time.

“We are grateful for the federal district court’s permanent injunction and judgment halting the implementation, application, or enforcement" of the NIH cap, the Association of American Universities, which is a plaintiff in the case, said Saturday in an update on the NIH saga.

“The court’s injunction, previously temporary, will continue to apply to all institutions nationwide,” AAU added.

Kelley, a Biden appointee for the U.S. District Court in Massachusetts, has blocked NIH from instituting its indirect funding cap almost since the agency issued it in February. Multiple groups of plaintiffs sued over the cap, including more than 20 mostly Democratic state attorneys general as well as higher education groups, universities and others.

The NIH decision restricted its reimbursements for indirect costs to 15%. Research institutions previously have negotiated individual indirect cost rates, at an average of 27% to 28%, according to NIH. Those indirect costs include overhead expenses such as for buildings, laboratories, administrative staffing, equipment and utilities.

The agency said at the time, however, that the cap would “ensure that grant funds are, to the maximum extent possible, spent on furthering its mission.”

An attorney for NIH during a March hearing said the funds would be redirected to direct research activities, which contradicted an agency post on social media about saving $4 billion when it issued the guidance.

But plaintiffs in the multiple lawsuits filed against the agency have argued that NIH lacks the authority to unilaterally cap indirect cost funding, especially given that a 2018 statute specifically blocked the agency from altering reimbursement rates.

Despite Kelley’s orders barring NIH from carrying out its cap, the agency has already created widespread disruption in the research university world. Institutions from Columbia University to the University of California system have frozen hiring and taken other preemptive budgetary measures to maintain flexibility as they brace for slashed federal funding on several fronts.

The NIH cuts would land hard for many. For example, a 15% cap for indirect funding would mean a loss of $121 million at University of California, San Francisco, $136 million at Johns Hopkins University, $129 million at University of Pennsylvania and $119 million at University of Michigan, according to a New York Times analysis.

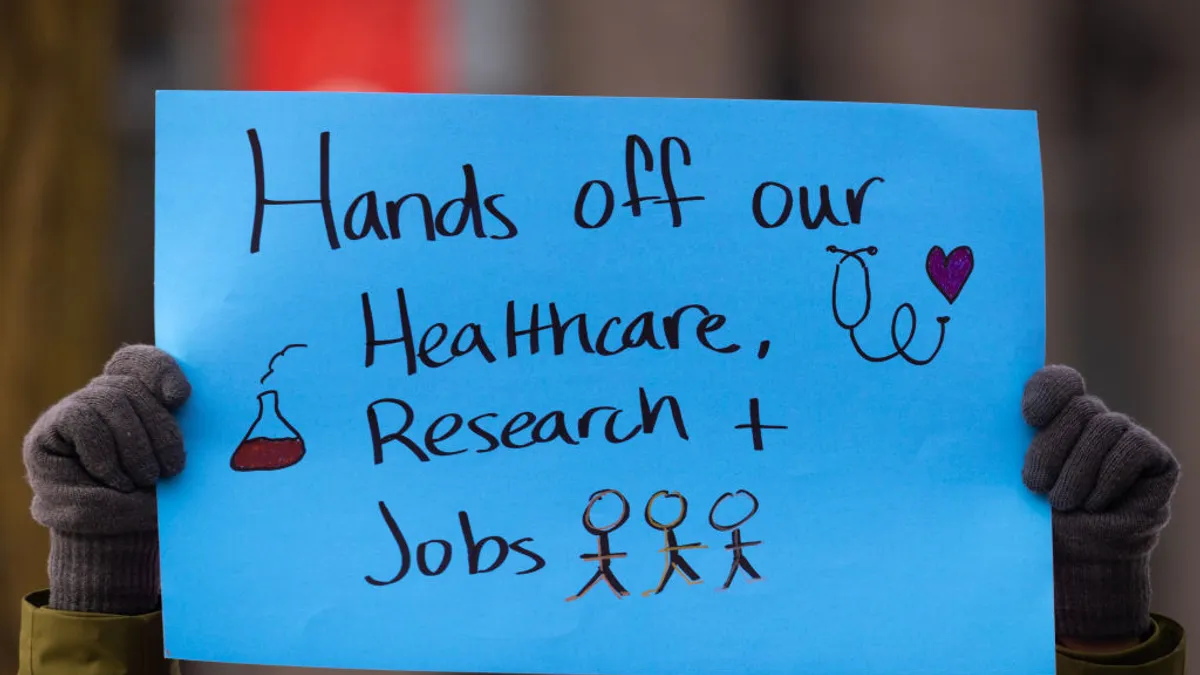

Universities have warned about dire impacts from the funding cuts. Ultimately, Kelley agreed with plaintiffs' descriptions of the harms that would be caused by NIH’s cap. The move would hit grants already in progress and result in, in Kelley’s words from March, “the loss of jobs, the suspension of research, including clinical trials and infrastructure projects, and a reduction of teaching staff who are committed to cultivating medical students.”