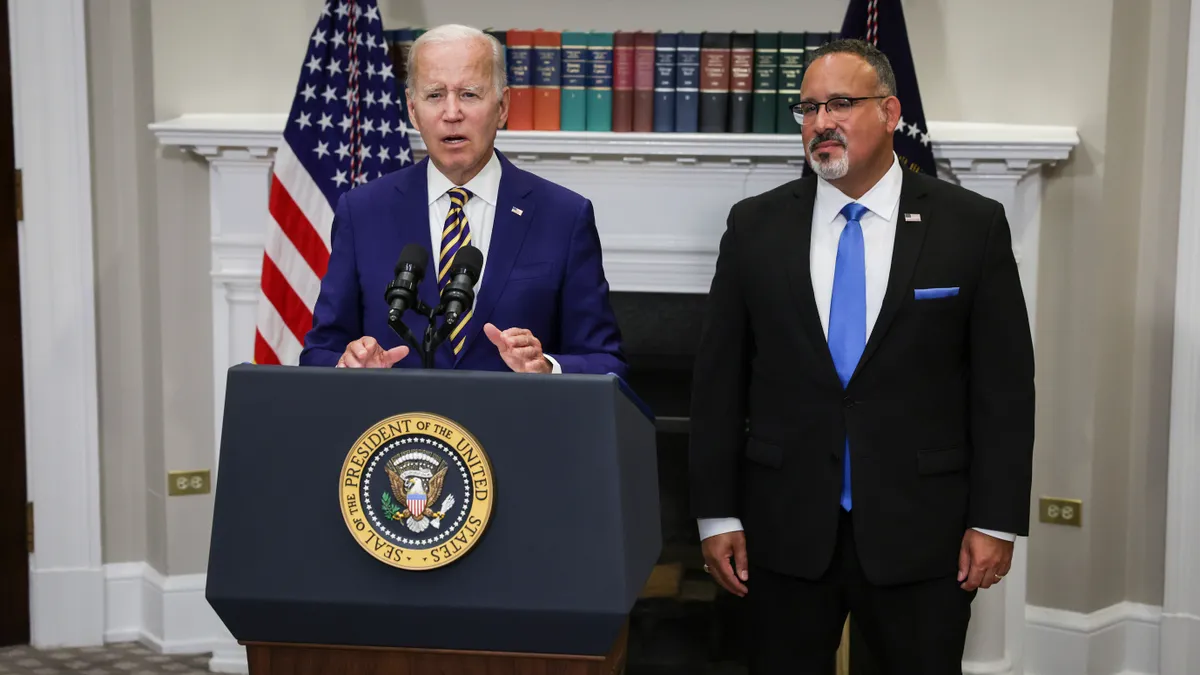

President Joe Biden invited plenty of debate Wednesday when he announced an income-capped student loan cancellation plan, which will wipe out as much as $10,000 for most borrowers and $20,000 for federal Pell Grant recipients.

Higher ed associations and some college leaders chimed in with support. So did Democratic lawmakers like Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York. Meanwhile, conservatives castigated the move, with Rep. Virginia Foxx, a Republican from North Carolina who is ranking member of the House Education and Labor Committee, calling it a "$300 plus billion transfer of wealth to the 13 percent of Americans who have student loans."

To dive into the substance of critiques — and what they mean for colleges — we spoke with Beth Akers, an economist who is a senior fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. Akers coauthored the 2016 book "Game of Loans: The Rhetoric and Reality of Student Debt."

She's also written critically of student debt forgiveness throughout the lead-up to Biden's announcement. Loan cancellation “creates an implicit guarantee that future students won’t be on the hook to pay back what they borrow,” she wrote in May. That could drive up both demand for higher ed and college prices.

“We tend to think of colleges and universities as benevolent institutions, but they are also economic entities that must respond to the incentives in front of them in order to survive," she wrote. "So it won’t just be predatory institutions that raise prices in response to this run-up in demand — it will be all of them.”

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

HIGHER ED DIVE: What did you think of the debt cancellation announced Wednesday?

BETH AKERS: Very generally, I'd say it could have been worse. The plan seemed to address some of the concerns that conservatives have voiced about the idea of loan cancellation with the introduction of income limits, as well as the extra generosity toward Pell recipients.

That said, I still think it was the wrong approach for addressing the challenges in higher education. It did nothing for fixing the systemic issues that got us here, and I'm concerned that it exacerbates the challenges that we're already dealing with.

What, specifically, is problematic?

There are all sorts of what I'll call intertemporal fairness issues that are created by the one-time nature of this event, which is another way of saying if somebody paid off their loans yesterday, they got nothing from the plan. If someone used cash instead of borrowed, they get nothing.

I think most concerning to me, though, is what this does to future incentives. We have basically sent a message to borrowers now that you won't necessarily be on the hook to repay all the money that you borrowed to pay for school. We don't know how future students will respond to that information and how they're going to change their willingness to pay for college and their willingness to borrow, but it only pushes in the direction of increasing willingness to pay and people borrowing more than they would have otherwise.

That's essentially an increase in demand for higher education services which will yield higher prices in the long run.

This is the moral hazard argument you've been writing about. It's been used in discussions about other types of debt in the past, but it raises some interesting questions when applied to student loans. First, is it applicable to college students who don't have experience with debt?

I don't think that college students considering how much to pay for college, how much to borrow for college, are necessarily acting like the characters in our economic textbooks. They're not doing the detailed cost-benefit analyses like we economists would imagine or hope they'd be doing.

We know they're using rules of thumb. They have emotional decision making.

That can go in either direction here. Either that means that this is just a blip and doesn't make a big difference about how they think about paying for college, or this is something that sticks with them and they're willing to pay a lot more than they would have otherwise.

There's nothing like this that has happened before that would allow us to have a basis for estimating how people will respond.

It's possible that the effect is modest to negligible, but I don't see in any way how it pushes in the right direction, which is for people to be more conservative about what they're spending and borrowing. It only has potential to make that dynamic worse.

Is it possible particular segments of the borrower market could behave differently — that low-income students could remain leery of taking on debt while high-income students believe future forgiveness is more likely and become more open to borrowing?

Yeah, exactly. If you take as given the amount that someone is going to spend on college, then there becomes the decision: If you have the resources, do you pay for it out of what you have?

Certainly, I think somebody who has the means to pay for college out of other resources would be encouraged to borrow now, because interest rates are low, and there's the chance that they might not have to pay it back.

Economists would say there are margins which we can see where there would very likely be changes in behaviors, and others less so. Economically challenged students may not be willing to take that gamble, and it may make no difference at all to them in terms of what they are willing to pay. Or they may have been borrowing maximum levels anyway, so there is no room to budget there.

I think there will be a heterogenous effect but all pushing in the same direction.

Why should college leaders care about this decision involving a federal program and borrowers?

In an ideal world, I would like to say that this is information that's not relevant to them. If we believe that institutions are these benevolent organizations that only seek to contribute to society and help students better themselves and become these quote-unquote global citizens that the mission statements often talk about, then this information is irrelevant.

But we know that institutions operate and respond to economic incentives, because they are rational and because they face the economic constraints that all institutions face.

And so I think what will likely happen is that without intending to, these institutions will be on the receiving end of, potentially, more aggressive demand from their students to pay and get into those seats at their colleges.

This is good news for them. I think it's essentially a backdoor subsidy to those institutions, and whether they're saying it publicly or not, I think they're probably pretty pleased with the outcome.

Does this add reputational or political risk?

You could say that colleges should be scared, because this is kind of a vote of no confidence in the service that they provide. We're saying in some way, we're letting people borrow to go to these institutions, but if they need a bailout, something's wrong at the colleges and universities.

I don't think a lot of people are perceiving the news in that way. Some people are questioning why college is so expensive and how we address that. Maybe there will be some negative blowback that institutions face as a result of this, but altogether I think we have this unrestrained belief that these institutions are doing good, whether the numbers prove it out financially or not.

So it doesn't seem like there's a tremendous risk for institutions. We hold them on that pedestal of being sort of above the economics of the transaction they're involved in.

If you'll indulge a hypothetical, let's say you're a leader in Congress and can whip the votes for student loan policies you want. What is your preferred set of reforms?

I wish we had taken the 2 1/2-year pause on loan repayment to fix the system of repayment so everybody is on a single, universal, income-driven repayment program that's easy for borrowers to use. It's easy for the Department of Education to administer, and it's transparent, so when people take on their debt, they anticipate what will be available to them and compare and contrast that so that they won't have to face an unaffordable loan payment.

To me, that would have taken pressure away from the White House to do anything like the loan cancellation event we saw.

Secondly, I'd probably address graduate student lending by putting either more aggressive constraints on what students could borrow or eliminating graduate student lending altogether from the federal student loan portfolio.

What did we miss?

People keep asking, "Where do we go from here?" and, "What's next?"

I keep saying the same thing, which is that I think we need to alleviate some of the demand for higher education, which colleges won't want to hear me say.

This idea is that we need to make sure that there are pathways to a career outside of higher education, because that will take the privilege away from institutions to continue to raise prices year after year without necessarily delivering a commensurate value.