Shortly after Tim Sands took over as Virginia Tech's president in the summer of 2014, he tasked a group of staff and administrators with dreaming up an "innovation district" that could help fulfill his idea of what a modern land-grant university should be.

The idea for such a district — which took its name from a Brookings Institution report — was to expand the primarily rural university's footprint in urban areas and in fields where the economy was growing. It would create a venue where "talent and space and ideas" would be "colliding," said Steve McKnight, vice president for Virginia Tech's National Capital Region, who led the team working on the innovation district concept.

A couple years in, the team had identified needs in the Washington, D.C., area and ideas were taking shape. "The pace and velocity were going to be determined by our ability to find a partner to help support it," McKnight said.

And then, in a lucky bit of timing, along came Amazon.

Administrators say the inter-city competition for the e-commerce giant's second headquarters (dubbed "HQ2") accelerated plans already in discussion to increase Virginia's tech talent pipeline and the presence of state universities in the Washington, D.C., region. The race to lure Amazon helped give those plans form and political momentum.

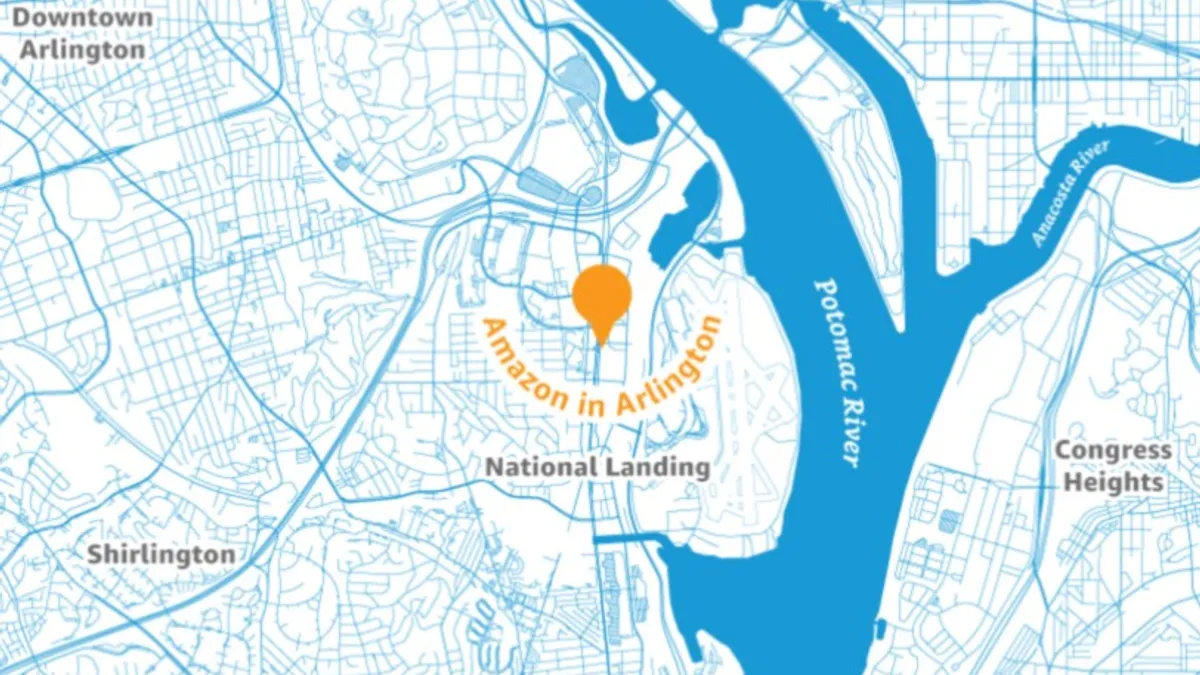

Now, with Amazon's decision, announced mid-November, to place half of HQ2 in Northern Virginia — and with it, 25,000 high-paying, largely tech-focused jobs — the plans are actually in motion. But the effort to recruit faculty, donors and corporate partners is just beginning.

"The truth is, this was a highly unusual opportunity, and we weren't sure we would win until the day it was announced," said Brandy Salmon, Virginia Tech's associate vice president for innovation and partnerships. "So there's been a lot of work on the concept design and the need, and how we can fulfill that. But this is still sort sort of Day Two, and there's still a lot of work to be done."

For its part, Virginia Tech plans to build a $1 billion, 1 million-square-foot, tech-focused Innovation Campus in Alexandria, Virginia. It is largely modeled on and inspired by Cornell Tech in New York City (a campus credited with helping the city land the other half of HQ2). The university plans to enroll the campus's first 100 master's students next year in a temporary space. That's expected to increase to 500 within five years, and would ultimately grow to 750 master's students, as well as hundreds of doctoral students and postdoctoral fellows, once the campus reaches scale. The university and state have each pledged $250 million to seed the project.

Also in the wake of Amazon's decision, George Mason University announced plans to add some 500,000 square feet to its Arlington, Virginia, campus and more than double its graduates in computing programs to 15,000 by 2024. As part of the effort, George Mason also plans to add a School of Computing, as well as a think tank and incubator focused on the digital economy. The university and the state have each pledged $125 million toward the computing programs.

'Not (only) about Amazon'

According to higher ed leaders in the state, their planning ahead of HQ2 was a matter of good timing and opportunism. "Obviously, this was the biggest economic development opportunity we would see in our lifetime, maybe a couple of lifetimes," said Stephen Moret, president and CEO of the Virginia Economic Development Partnership (VEDP).

Early on, Moret saw that higher education needed to be a key part of the package of goodies offered to Amazon. That was partly from past work with tech companies, where access to talent "is by far the biggest driver of their location decisions," he said.

It was also partly out of political necessity, in a state that Moret noted is not known for large tax and financial incentive packages relative to other southern states. Soon after Amazon released its initial request for proposals, Moret started polling higher ed leaders across Virginia about how higher ed could become a centerpiece of the state's proposal.

But officials who worked on the proposal say the higher ed plans weren't created in a vacuum to the sole benefit of Amazon or as an added subsidy to the company. "The campus is not about Amazon," said Natalie Hart, Virginia Tech's assistant vice president for advancement in the National Capital Region. "It's about Amazon and others."

"Amazon completely aligned with our own strategic thinking," McKnight said. "We were ready." He added that Virginia Tech's plans for expansion considered two years ago and those drawn up during the HQ2 scramble were "comparable," if some subfields within computer science and engineering taught at the Innovation Campus might differ with Amazon now coming to town.

"The truth is, this was a highly unusual opportunity, and we weren't sure we would win until the day it was announced."

Brandy Salmon

Associate vice president for innovation and partnerships, Virginia Tech

Deborah Crawford, George Mason's vice president for research, said Amazon provided a catalyst but wasn't the plan’s exclusive driver. George Mason already had a sizable computer science footprint in the region. Without Amazon in the mix, the School of Computing launch might have been a year or two further out, she said, noting that the company's arrival has "not really changed" the scale or content of the plans. "We had been talking about creating a college in computing based purely in strength of numbers and outcomes."

In the 2017-18 academic year, Virginia Tech churned out roughly 389 graduates with computer science or related bachelor's or master's degrees, and George Mason produced 248 degrees, according to a VEDP presentation. Virginia was already a top location of information technology talent, with a higher concentration than California, Massachusetts or Washington state, according to a state presentation from September 2017, though it had a larger relative talent gap than those and other states. Further, a December 2016 report from the Northern Virginia Technology Council found Virginia had nearly 40,000 software developers as of early 2016 — a figure that was expected to grow well before Amazon set off a courtship scramble.

Even with an identified need for more tech education, Virginia officials were interested enough in Amazon's specific needs to make a deep study of the kinds of jobs it would need to fill and the educational background of its current workforce. Research included scrubbing the company's job postings and the social media profiles of its employees in Seattle. In the latter case, VEDP learned that roughly half of all Amazon employees identified in the research who were working in tech-related positions held computer science degrees, by far the most widely held degree among those workers.

From plan to delivery

Drawing up the plans for Virginia Tech's Innovation Campus took more than a year of concerted effort and coordination. Now comes the hard part.

The physical space at the proposed Alexandria site still needs to be designed. It also needs money to build it and — more importantly — to staff it with educators and researchers. Salmon offered no details on faculty recruitment, saying planning around hiring numbers and the timeline is happening "in real time."

Hart expects the $250 million Virginia Tech is on the hook for to be made up of incremental grants, industry partnerships and philanthropy. However, the university does not yet have a firm grasp on what the precise makeup will be as conversations with donors and partners are just beginning.

The state is expected to vote on its portion of the financing in the next legislative term and has already gone through a committee that vets big economic development packages, indicating support from key legislators and the governor, according to Moret.

It's not clear yet whether the second half of the campus's $1 billion price tag will include state funding. Hart said she does not anticipate funding the last $500 million "being a problem" and expects additional philanthropy and partnerships to help meet the need.

A core delivery team of about 10 people at Virginia Tech have been working to make the Innovation Campus plan a reality, with others in the university also contributing time and insight, Salmon said. She offered few details about the team's immediate tasks but said they were broadly working to make sure "programs meet marketplace needs" and include experiential learning opportunities.

Hart said she has been working with a "small group of philanthropists and thought leaders" on "high-level strategic issues" around the future campus' needs. Bringing in talent at the faculty level is the top fundraising priority for her team at the moment, above funding capital costs for the campus, she noted.

On the agenda for the spring are events such as town hall sessions aimed at "educating" alumni and business leaders about the campus, Hart said. The events could lead to fundraising opportunities, but that is not their point, she added: "We want and need people's help and engagement."

University and state officials explicitly drew inspiration from Cornell Tech when considering what the Innovation Campus could be and its role in the region. The New York Times described Cornell Tech in a recent article as "one of the most visible symbols of New York City's booming technology sector — and a major selling point in the bid to persuade Amazon to build a headquarters in Queens." The Times also noted that students and researchers at the campus have created 50 startup companies and raised $60 million from investors.

Virginia Tech had the advantage of access to high-level staff who played a role in Cornell Tech's creation. They include Charlie Phlegar, Virginia Tech's vice president for advancement, who previously served as chief fundraiser at Cornell, heading up a $6 billion campaign and serving on the steering committee that pushed the formation of Cornell Tech. Hart said Phlegar and others helped the proposal team in the planning process and in knowing what to expect while building a tech-focused higher ed hub from the ground up.

All options on the table

Six months from now, Hart expects the delivery team to be further along in campus design and readying to enroll students. There could also be talks by then around initial corporate partnerships and lead gifts, she added.

Less clear, at this point, is what the university's relationship will look like with the company that largely catalyzed these plans and sparked state and higher ed leaders into action.

One reason why that's hard to forecast is university administrators don't know yet which units and staff from Amazon will be housed in Northern Virginia's half of HQ2. George Mason's Crawford said the sort of work being done at Amazon's facilities in the area determines the kinds of research partnerships that might result. It could also influence the coursework in that university's computer programs, she said.

As for the types of partnerships that might result, Crawford said "all options are on the table" and could include "entrepreneurial" activities with students. She points to the University of Washington, in Amazon's hometown of Seattle. Among other partnerships with the company, it hosts an Amazon Catalyst program that offers monetary awards to pursue new product and service ideas.

At Virginia Tech, the future with Amazon — beyond obvious expectations of a heavy recruitment presence — is still foggy. "At this point, it is a little premature to say what it would look like with Amazon," Salmon said. "We would love to strike partnerships with Amazon and other research partners." Hart said it is "to be determined" what sorts of partnerships Virginia Tech might enter into with Amazon and how curriculum at the campus might meet its talent needs.

Salmon noted that the university has "all sorts of partnerships with industry," including research sponsorship, commercialization and licensing — what she describes as a "discovery-to-market" model.

A 'robust' need, even without Amazon

Both Salmon and Hart said Amazon isn't expected to be the campus's only corporate partner. Indeed, plans for higher ed investment in Northern Virginia and the computer science degree pipeline before HQ2 came along show the broader demand for tech graduates.

For his part, VEDP's Moret has no worries about the state's ability to fill that pipeline, noting that colleges there have more demand from qualified students than they have capacity to take on. "If anything, my concern would be we aren't doing enough," he said.

And what if Amazon doesn't show up, at least not in the numbers projected?

The state considered numerous risks to Amazon's stated plans, including scenarios where the competitive landscape shifts, the company is sued by antitrust enforcers or it doesn't bring the projected number of jobs. But on the higher ed side, officials have made clear the investments are important to the state, with or without Amazon.

"If Amazon weren't coming, we would have proposed doing something similar anyway," Moret said. "The need for these programs is very, very robust even in the absence of Amazon. In reality we'd really like to go faster than what we've already laid out."