Dive Brief:

- The primary industry group representing for-profit colleges, Career Education Colleges and Universities (CECU), last week sent a letter to key Democratic leaders that asks for help making it easier for third parties to take over failing institutions and allow financially struggling colleges to retain access to student aid.

- CECU President and CEO Steve Gunderson addressed the recent closures of Education of Corporation of America (ECA) and Vatterott in the letter to Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Reps. Elijah Cummings, D-Md., and Suzanne Bonamici, D-Ore. Gunderson noted colleges that file for bankruptcy are cut off from Title IV funds and argued this can prevent them from reorganizing or being taken over by financially healthy operators.

- Gunderson framed the letter — which follows a probe the Democratic leaders opened into ECA's abrupt shutdown — around the need to protect students, writing "abrupt school closures is an issue requiring immediate attention on both the legislative and regulatory fronts."

Dive Insight:

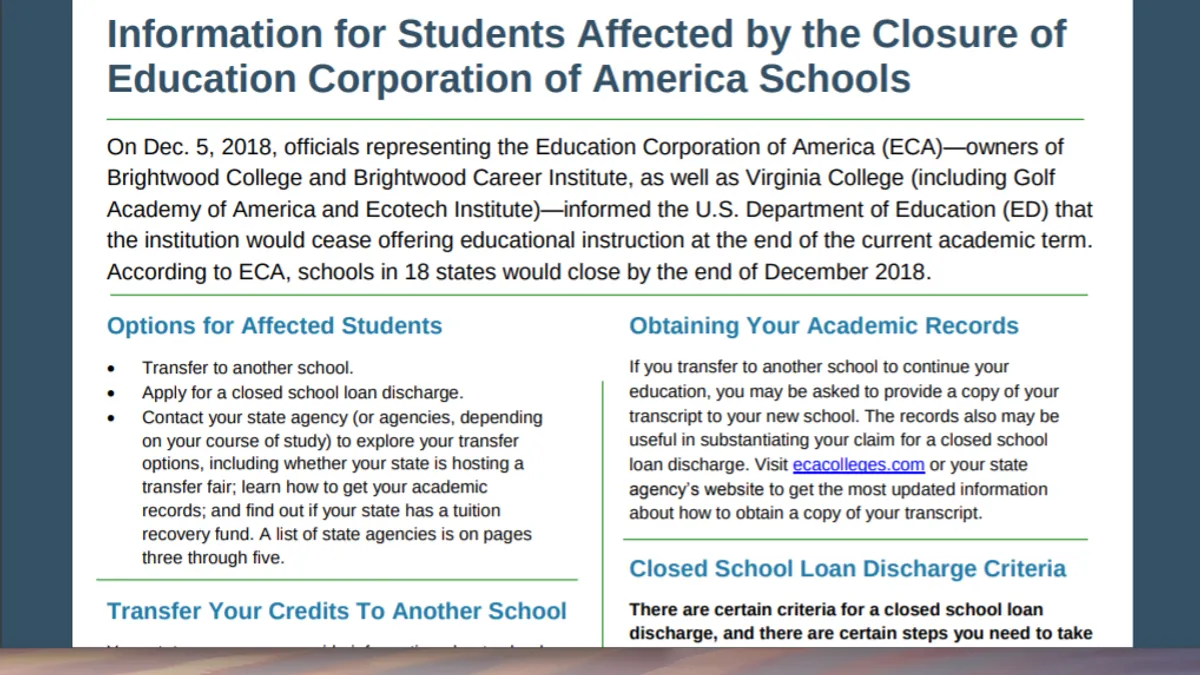

ECA's sudden closure was indicative of broader issues in the for-profit sector and raised far more questions than the company or regulators have been able to answer so far.

Chief among those questions was why ECA had no teach-out plans in place and why the shutdown was so sudden. (Some employees have said they were just as clueless about the closure as students and several have sued ECA over alleged failures to give legally required warnings about the layoffs.)

Gunderson's points about bankruptcy were made generally, however, in an argument for what his group sees as needed reform to statutes and regulations. But ECA was a useful case. The company in October sued the Education Department and requested a court-appointed receiver in an effort to avoid bankruptcy.

In its response to the lawsuit, the Ed Department said ECA had no legal basis to sue the agency. ECA could have dealt with its creditor problems — including landlords that were threatening eviction as ECA's financial problems mounted — through bankruptcy court, but it would have meant losing access to Title IV funds. Instead, the department argued in court papers, "Plaintiffs seek to have it both ways: they want the benefits of bankruptcy (the bankruptcy stay and the centralized administration) without the burdens (the potential loss of federal funding)." A judge ultimately dismissed ECA's lawsuit.

Gunderson raised another issue that pertains directly to ECA's case: the Ed Department's heightened cash monitoring (HCM) system, which restricts an institution's access to federal student aid in cases of accreditation, financial, administrative and other concerns.

According to figures Gunderson cited, about half of the schools on HCM1 or HCM2 are for-profits. In the case of the stricter system, HCM2, Gunderson wrote that for-profits were disproportionately affected, "as evidenced by the fact 45 percent of proprietary institutions on HCM2 as of December 1 have since closed while 0 percent of public and non-profit institutions have since closed." ECA was among those that closed, the Ed Department having placed the company's schools on HCM2 in November. ECA's president said this, as well the suspension of accreditation, led to its shutdown.

All stakeholders have agreed publicly that protecting students from sudden closures is a top priority. ECA, the Ed Department and CECU have all lamented how difficult the for-profit operator's sudden closure was for students.

But ECA and other stakeholders had divergent views over the cause. And Warren, who has urged the department to revoke ACICS's federal recognition, along with other congressional leaders may well have their own view of what went wrong. That's a sign finding a policy solution to the underlying problems won't be simple or conflict-free.