This is part one of a two-part series on the sudden closure of University of the Arts. For part two, click here.

PHILADELPHIA — Sometimes it takes a closure to remind us just how public a private college’s institutional importance actually is.

This year has seen the winding down of several historic private colleges, including Wells College in New York and Goddard College in Vermont. Announcements of their closures sparked shock, grief and dismay.

Arguably, the most dramatic closure came at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia.

In June, the nearly 150-year-old institution’s life came to a sudden, shocking end when it shuttered with just a week’s notice. The event is still reverberating in the city to which UArts belonged, its closure a public trauma. The announcement sparked protests, media and legal investigations, multiple lawsuits and other legal actions, and the swift departure of the university’s top executive.

UArts may have shared many of the same financial travails as other private colleges around the U.S., but also like those others, its life was singular. And replacing it or filling the gap, or somehow reviving it, won’t be easy.

UArts and its historic campus sit in the heart of Philadelphia’s arts district. Today it stands vacant but for security staff. Its loss is the city’s as well, given the university’s active, long-running role in Philadelphia’s arts world.

“The city is going to be lamer in 15 years,” said Daniel Pieczkolon, president of United Academics of Philadelphia — which represents UArts faculty and staff — and a professor at Arcadia University, located in a suburb near the UArts campus. “Philadelphia has a great arts culture. UArts is not the sole reason for that, but it is emblematic of it.”

While the city learns to live without UArts, and its legacy lingers in a sort of higher education limbo, the battle over its closure goes on, with various stakeholders fighting for money — and answers.

They pulled the carpet out

At a town hall in April, then-President Kerry Walk had good news for UArts faculty: A year-and-a-half-long enrollment push was paying off. Aggressive targets had been surpassed.

Bradley Philbert, a former UArts lecturer and a UAP official who helped negotiate with the university, described a sense of relief among faculty.

Yearslong negotiations had culminated in the union’s first faculty contract in February. And now an enrollment crunch seemed to be behind the university — with a strong incoming student population for the 2024-25 year.

Still, overall numbers were down after some tough years for a college heavily dependent on tuition. Between 2017 and 2022, fall headcount declined 29.4% to 1,313 students, according to federal data.

In October 2023, Walk held a meeting with the university’s top leaders, including deans, in which she discussed serious financial issues, according to an August report from Philadelphia magazine. But in the months following, the deans received no major updates on the institution’s financial situation.

In other words, Walk’s silence combined with the sunny enrollment numbers gave deans at the meeting reason to think things were looking up. And no one in the rank and file had any idea permanent closure was just around the corner.

Yet it was. And a brooding question mark still hangs over the university’s collapse.

The public releases announcing the closure were conspicuously short on details. A statement from Walk and UArts board Chair Judson Aaron on May 31 alluded, vaguely, to “a cash position that has steadily weakened” that meant the university could “not cover significant, unanticipated expenses.”

They added: “The situation came to light very suddenly. Despite swift action, we were unable to bridge the necessary gaps.”

Today, the public doesn’t know much more than that, at least not with any certainty. Philbert pointed to water maintenance issues in the university’s Terra Hall, a building originally built in 1911 as a Ritz Carlton hotel, but nothing amounting to an institution-killing expense.

The university’s most recent financials date back to the fiscal year that ended in June 2023. They show a total operating deficit of about $12 million, a sharp drop from the more than $1 million surplus the prior year. The swing to an operating loss followed a decline of more than $4 million in tuition revenue and a roughly $5 million dip in revenue from government grants.

Meanwhile, at $3.9 million, the university’s available cash was roughly half what it was the year before, even after it began drawing on a line of credit.

The dizzying speed from announcement to closure and the lack of transparency has led to widespread, lasting anger. How could a sudden, dire shortfall of cash just appear? If leaders truly didn’t see financial implosion looming, why didn’t they? And if they did — why didn’t they tell the campus community?

“Somebody lost their moral compass in letting the school fall to its demise right now,” said Carol Moore, a former associate dean at UArts and founding director of its fine arts master’s in studio art. “It feels like a total abandonment. It didn’t happen overnight. The decision to abandon it with seemingly no sense of conscience or responsibility is what makes it so tragic.”

Or, as Jared Blando, a freelance illustrator and UArts alum, put it, “They pulled the carpet out from pretty much everybody.”

‘All of Philadelphia deserve answers!’

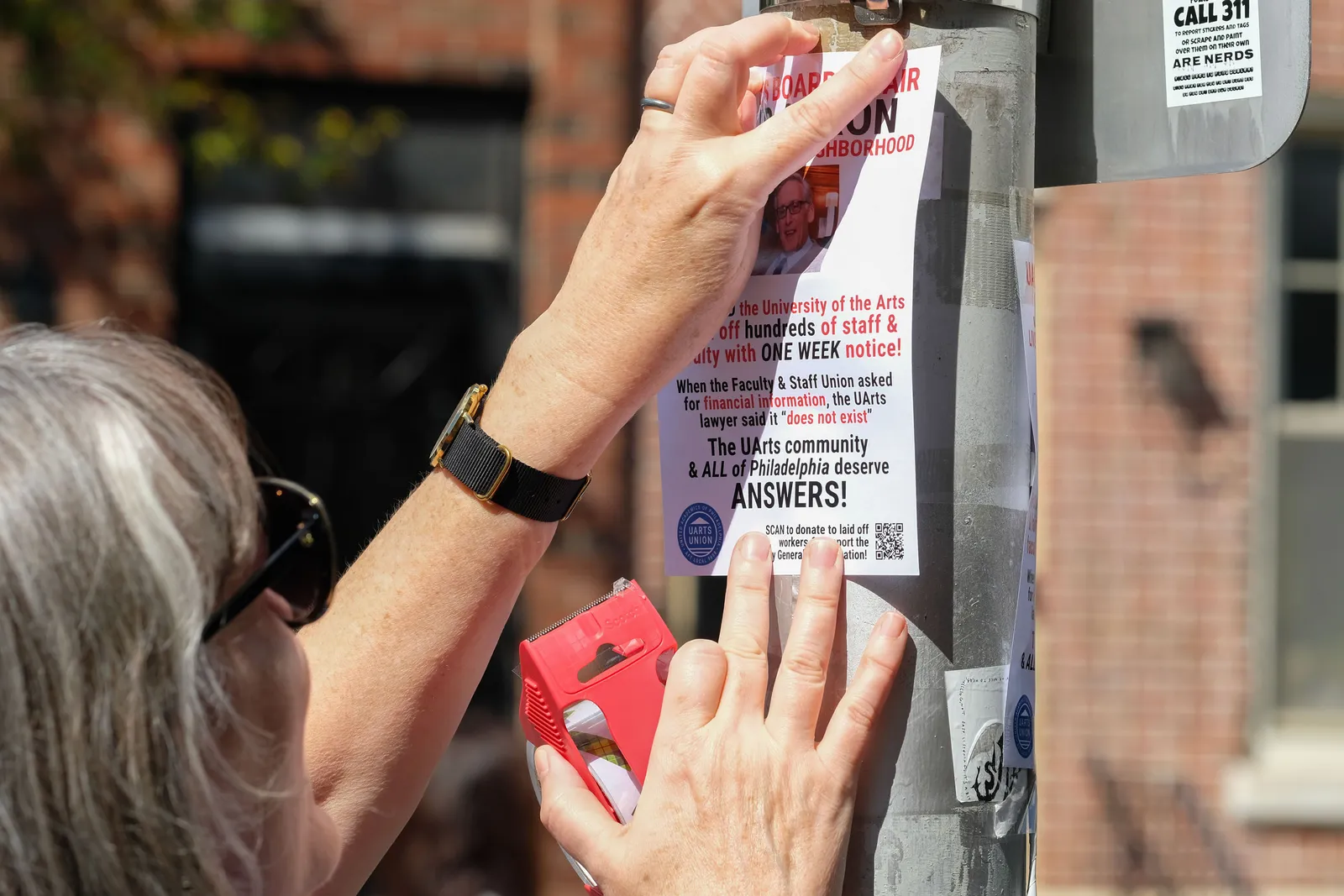

On a sunny afternoon in late August with teasing early-fall temperatures, a handful of UAP members, including Philbert, met at a park not far from Aaron’s residence in south Philadelphia.

They came with rolls of tape and dozens of flyers bearing a headshot of Aaron. In all capital letters, the flyers noted, “UARTS BOARD CHAIR JUD AARON LIVES IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD.”

The flyer went on to state — in red and black type for emphasis: “He CLOSED the University of the Arts & laid off hundreds of staff & faculty with ONE WEEK of notice! When the Faculty & Staff asked for financial information, the UArts lawyer said it ‘does not exist.’”

This was roughly the fourth time UAP members had posted flyers in Aaron’s neighborhood since the institution shuttered. Over the next half hour or so, the former faculty and staff taped the flyers to lampposts and street signs, put them on car windshields, and otherwise posted them to just about any available open surface where they might be seen.

Aaron did not respond to messages requesting comment sent through the university and its attorneys.

Charis Duke, a staff accompanist for UArts before it closed, entered a barbershop to ask if she could tape a flyer on the outside window. With permission secured, she headed back out, stopping briefly to try to comfort a child crying in anticipation of a haircut: “You’re going to do great!”

Duke said that she loved her job at UArts but saw problems in the institution and with the effectiveness of its administration, issues she said drove staff and faculty to unionize in recent years.

In public statements, including on the flyers, the union has placed blame for UArts’ closure squarely with management.

As the union members discussed future union actions following the afternoon's flyer-hanging, a man stepped out of a BMW SUV and studied one of the flyers they had posted.

“Are you doxxing this guy — is that what you’re doing?” he asked the group.

Several people jumped in at once to answer him, arguing that the flyers didn’t include Aaron’s address or contact information and therefore didn’t qualify as doxxing.

After some back and forth, and explanations of Aaron’s role in UArts’ closure, the man told the union members, “Get a life,” and got back in his car.

“UArts was our life!” one of the union members shouted back.

‘There’s all kinds of uprooting’

With UArts now permanently closed, UAP has essentially two goals at this point: Get compensation for faculty and staff who were hurt by the closure. And get answers.

During negotiations with the university in recent months, UAP has asked for minutes from board meeting discussions about the closure and other documents that could shed light on what led to the decision. So far, the university hasn’t provided those.

Another potential vehicle for both answers and compensation is a class-action lawsuit filed in June under federal labor law. The complaint alleges UArts did not provide sufficient notice to employees about job losses. Through the lawsuit, former UArts employees are seeking 60 days’ worth of wages and other benefits.

The lawsuit, were it goes to pre-trial discovery, could produce answers about who in the university’s administration knew what — and when they knew it. Philbert also pointed to reviews at the city and state level, including by Pennsylvania’s attorney general, that could provide information about the university’s last days.

The university's bankruptcy, filed in September, could complicate efforts to get payments for laid-off faculty and staff.

Potential claimants from the lawsuit were listed among the university’s unsecured creditors, who in a typical bankruptcy would be paid after secured creditors. Secured creditors in UArts’ case include bondholders and lenders whose claims against the university are secured by its property holdings.

Compensation is no small matter for employees. Because the closure came so abruptly and so late in the academic year, many faculty were left without replacement positions and headed into a fall semester with lost income, noted UAP President Pieczkolon. “It’s very scary.”

As many of the laid-off faculty were working artists, some picked up more work in their arts jobs. Others found teaching work. But Philbert noted that some full-time faculty at UArts — some with decades of experience — are now having to take on adjunct jobs elsewhere, often with fewer hours and lower pay.

“There’s all kinds of uprooting,” he said.

Of course, faculty and staff weren't the only ones whose lives were upended. Hundreds of students — with no warning — saw their education plans and often their finances turned upside down. Along with the challenges in finding new colleges to finish their degrees, some suffered immediate financial difficulties.

In a class-action lawsuit filed by former UArts students in August, plaintiffs said they lost job and educational opportunities at the university, as well as deposits and fees.

One of the plaintiffs, Abby Morehouse, worked as an office assistant at UArts and was slated to be a resident assistant for student housing for the 2024-25 year, which would have come with free housing and meals.

In addition, Morehouse majored in a theater production program at UArts that was among the few of its kind in the U.S. — and she lost the opportunity to have her work produced in a university-sponsored theater festival.

Morehouse was just one student among more than 1,000 affected. UArts’ closure brought multiple lawsuits, as well as protests, by students.

Philbert described a day of demonstration during the summer that drew some 1,200 students, faculty and community members, as well as news helicopters and national media attention.

“This was, briefly, the biggest story in Philadelphia,” he said.

Visuals Editor Shaun Lucas contributed to this story.