The U.S. Department of Education on Friday issued its long-awaited Title IX rule, which for the first time enshrines protections for LGBTQI+ students and employees, as well as pregnant students and employees, under the civil rights law that prevents sex-based discrimination in federally funded education programs.

"No one should have to give up their dreams of attending or finishing school because they're pregnant," said U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona in a press briefing late Thursday. "No one should face bullying or discrimination just because of who they are or who they love. Sadly, this happens all too often."

Among other changes, the new rule defines sex-based harassment as including harassment based on sex stereotypes, sex characteristics, pregnancy and related conditions, and gender identity and sexual orientation. It cements federal protections for LGTBQI+ students and employees that have swung between administrations for over a decade.

The regulations also broaden the conditions triggering Title IX protections by changing the definition of sex-based harassment from conduct that is "severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive," to either "severe or pervasive" conduct that must be considered both "subjectively and objectively offensive."

The new regulations also:

- Require that schools assume an accused student is innocent at the outset of an investigation.

- Give schools the ability to offer an informal resolution process, except in cases of student allegations against employees.

- Require schools to provide breastfeeding rooms for students and employees.

- Protect students and employees with medical conditions related to, or who are recovering from, termination of pregnancy.

- Revive the single-investigator model, which allows an individual to serve as both the case decision-maker and Title IX investigator.

- Provide more discretion to schools and colleges to tailor Title IX policies based on their size, age of students, and administrative structures.

- Make questioning at live hearings optional for colleges and universities.

- Have institutions largely rely on the "preponderance of the evidence" standard often used in civil lawsuits, making optional the "clear and convincing" standard.

- Change the definitions and requirements of a complaint to allow oral requests and not require signatures.

- Slightly narrow the previously widened pool of employees who must notify the Title IX coordinator of discriminatory conduct to excludeconfidential employees, such as guidance counselors or sexual assault response center staff.

- Provide postsecondary institutions flexibility to set their own reasonable time frames to allow parties to review and respond to evidence.

- Removes written notice requirements in elementary and secondary schools.

The rule's anticipated changes were expected to largely overhaul higher education requirements under the 2020 regulations put in place by former U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and make lesser tweaks to K-12 portions of the rule. Ultimately, many of the changes to higher ed and K-12 were preserved.

Significant delay from proposed to final rule

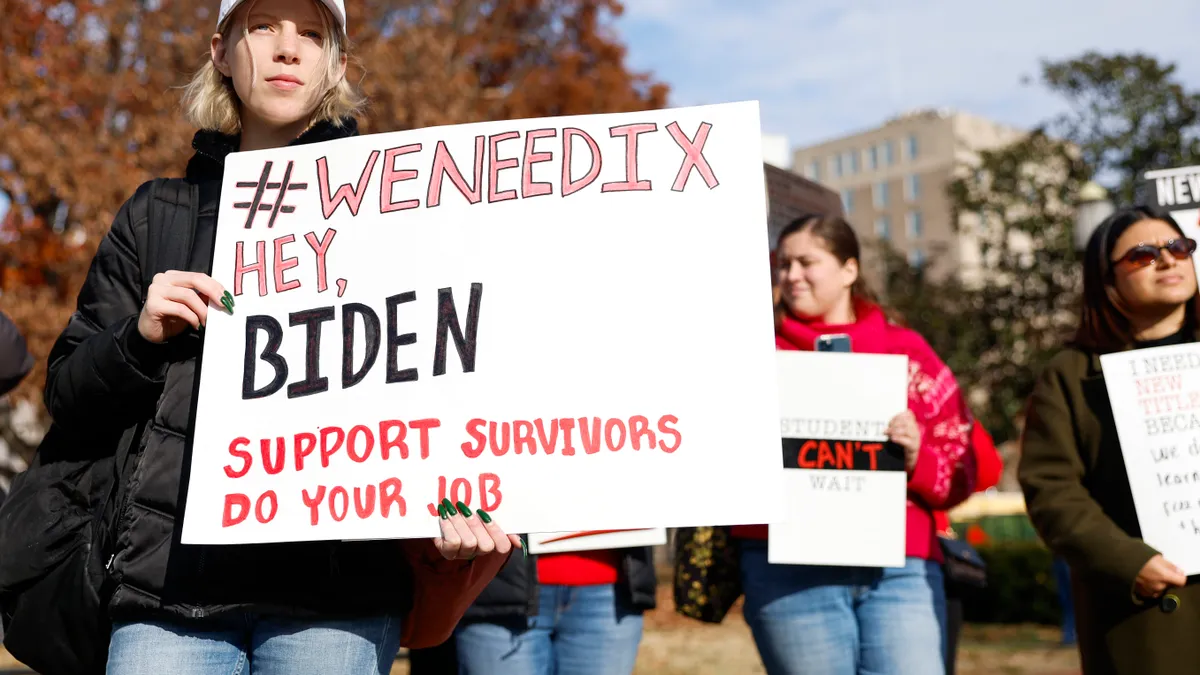

The regulations come after multiple significant delays in finalizing the Title IX rule that distressed civil rights advocates, who said the rights of LGBTQI+ students hung in the balance. The Biden administration issued the proposed rule in June 2022.

Supporters of that proposal pressed the Education Department to finalize it prior to the next school year. They also warned that the department could run into hurdles related to the Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to overturn certain federal agency actions within 60 congressional work days.

Had the department delayed the rule's release past spring, it was possible that period would have pushed beyond the end of the year, moving the review to a new Congress potentially hostile to the changes.

Though the department has likely averted that roadblock, other hurdles remain.

The Education Department's stance on Title IX garnered pushback long before the agency proposed the rule, and resistance is only expected to mount following its official release Friday.

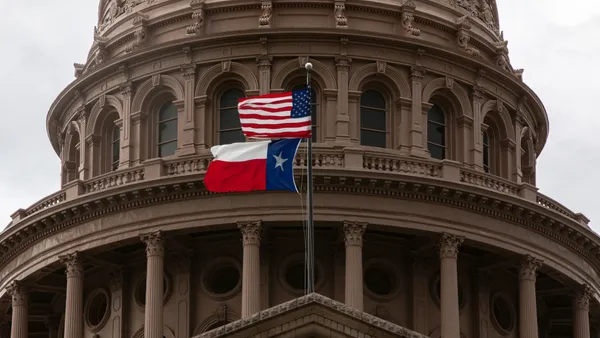

In September 2021, nearly a year prior to the proposed rule's release, 20 mostly conservative states sued the Education Department, seeking to overturn its interpretation that gay and transgender people are protected under Title IX.

Then, in April 2022, just prior to the proposal's unveiling, 15 Republic state attorneys general pushed the department to scrap its efforts to rewrite the 2020 regulation, threatening legal action. Those who opposed the 2022 proposed rule said it misinterpreted Title IX and would dramatically shift educational institutions' enforcement responsibilities under the federal law.

However, Cardona said on Thursday, "These regulations make crystal clear that everyone can access schools that are safe, welcoming and that respect their rights."

What's next?

The final rule is expected to be published in the Federal Register later this month, after which schools and colleges will have until Aug. 1 to implement it. The timeline mirrors the about three months that DeVos provided to districts for implementation back in 2020.

The department on Friday released alongside the rule a resource for drafting Title IX grievance procedures and policies that comply with the new regulations.

"These are designed to help schools speedily come into compliance," said Catherine Lhamon, assistant secretary of education for civil rights for the Education Department. Lhamon added that the guidance does not set out any additional requirements and said the department is available to provide technical assistance.

Meanwhile, the department's second much-anticipated final Title IX rule — on transgender students' involvement on athletic teams — is still under review in the Biden administration. The athletics rule garnered about 154,000 public comments — significant but still fewer than the over 240,000 received for the rule finalized on Friday.

The athletics rule, as of Thursday evening, had not yet made it to the Office of Management and Budget, which is required to review federal regulations prior to their release. OMB has up to 90 days for review once it reaches that office, with an option for a 30-day extension if needed.