Dive Brief:

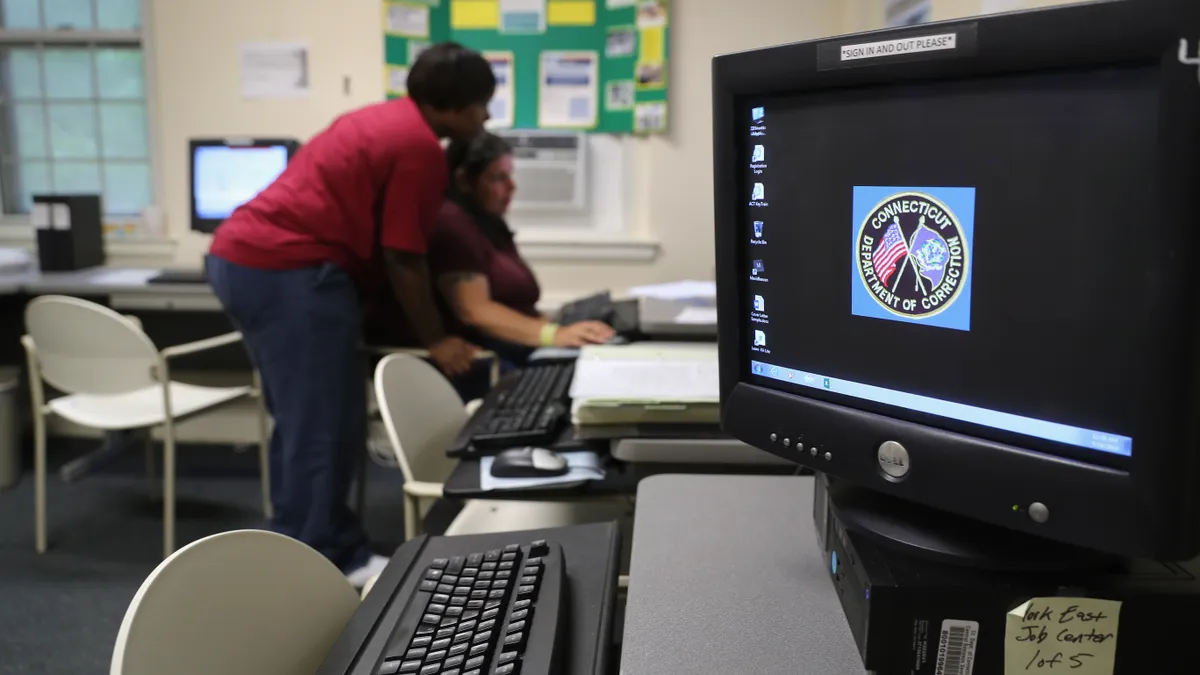

- To maximize educational opportunities and career pathways for incarcerated individuals, colleges should partner with state leaders and correctional facilities to implement a student-centered approach to prison education, according to a joint report from The Educational Justice Institute at MIT and the New England Board of Higher Education.

- The report recommends college and state officials create transfer credit agreements to show which institutions guarantee they will accept prison credits post-release, as well as those earned before students were incarcerated.

- College leaders should also work with their state's corrections commissioners to assess prison facilities and create a plan to most effectively use available space and resources for educational programming.

Dive Insight:

The report's recommendations come just as federal Pell Grants are about to open up to more people who are in prison.

Pell Grants, created to help low-income students pay for college, have been broadly unavailable to incarcerated people under a 1994 law. From 1972 to 1994, federal and state funds supported a majority of the roughly 772 higher education programs in prisons, according to the Bard Prison Initiative at Bard College. But after passage of the 1994 Crime Bill, many state lawmakers also pulled funds from postsecondary programs, essentially collapsing the prison education system.

Since 2015, the Second Chance Pell program has allowed select partner colleges to accept Pell funds for prison education programs. The U.S. Department of Education expanded the program multiple times and over 9,000 enrolled students had earned a certificate or diploma under the program as of 2021.

Beginning July 1, the Education Department will reinstate Pell eligibility for incarcerated students and allow them to use federal funds to cover the cost of eligible prison education programs. Roughly 2% of 1.6 million people in U.S. prisons are expected to use the Pell program, according to a 2022 government audit.

As of fall 2022, New England had about 43 prison education programs, 16 which were enrolled in Second Chance Pell, according to the report.

“We are seeking to change the conversation in higher education to become more inclusive of the prospective student population in prison," Lee Perlman, co-director of The Educational Justice Institute, said in a statement. "This is another group of students who need what higher education can offer and we must work across systems to deliver it."

In October, The Educational Justice Institute and the New England Board of Higher Education partnered to create the New England Commission on the Future of Higher Education. Commission members included regional higher education, workforce development, and corrections leaders, along with advocates and formerly incarcerated professionals.

The average length of a prison sentence is trending downward, largely due to rollbacks on mandatory minimums, the report said.

"Less-than-three-year average sentences mean that higher education institutions interested in offering programs in prison need to think critically about how coursework completed on the inside can be viable post-release," it said.

In addition to ensuring credits transfer to institutions students could afford to attend, researchers suggest that offering short-term and stackable credentials can help address the interruption in education. Colleges must also consider in-prison disruptions, including facility transfers, a process about which there is minimal publicly available data, the report said.

It recommends colleges employ education and career advisers who guide students during incarceration and after release.