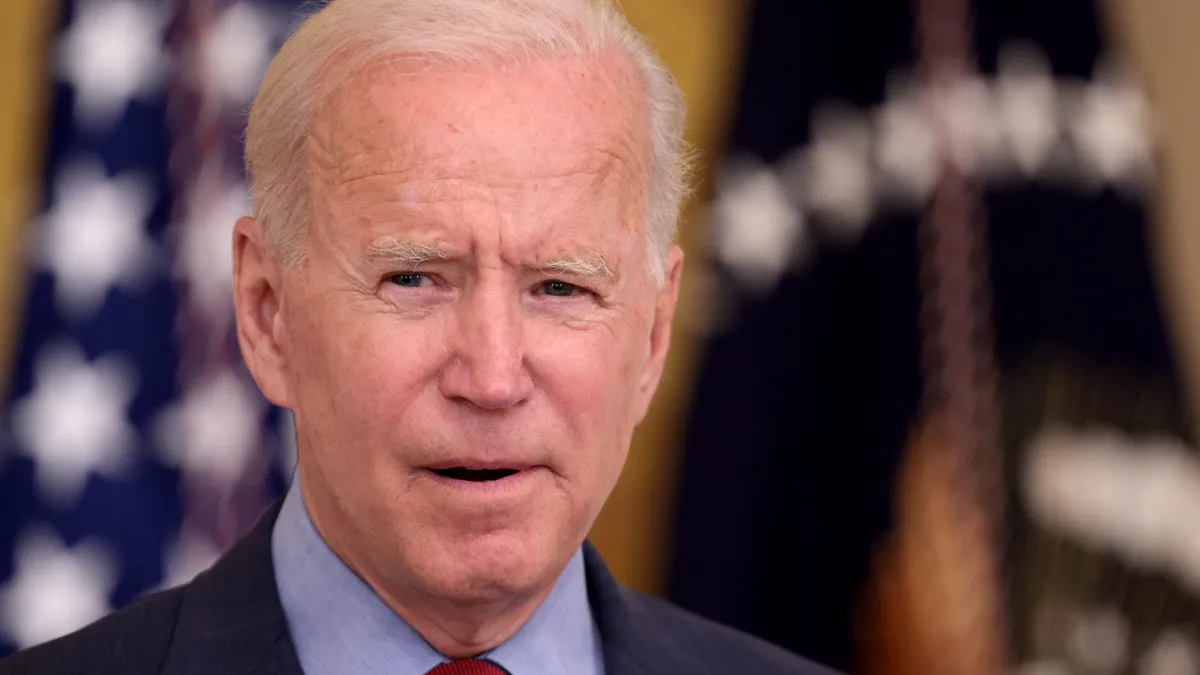

Months of failed haggling between the White House and the moderate Democratic wing over President Joe Biden's signature spending plan recently yielded a new, scaled back iteration — with a surprising inclusion.

Similar to the previous version of the Build Back Better legislation, it proposed additional investment in the federal Pell Grant, adding $550 more to the maximum amount and raising it to $7,045. The Pell Grant benefits low- and moderate-income students.

But this increase would only target students attending public and private nonprofit colleges, with those enrolled at for-profit schools excluded. This represents a radical departure in policy, as the federal government has never parceled financial aid by institution type.

Observers believe the administration is clumsily attempting to dissuade student interest in for-profit colleges, some of which have come under fire for saddling students with poor-quality degrees and mounds of debt. But many critics fear the shift will instead complicate the federal aid system and confuse students in their college searches as they figure out how much money they can receive.

"This is a big deal," said Robert Kelchen, a higher education professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Accountability tool or blunt instrument?

The provision in the $1.75 trillion package would be a step toward the Biden administration's goal of doubling the Pell Grant and help fulfill its desire to hold for-profit colleges accountable.

Biden was widely expected to take up the mantle of his Democratic predecessor, Barack Obama, whose administration used its regulatory might to crack down on proprietary schools. Former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos rolled back many of these policies, including one that punishes colleges whose programs leave students with unmanageable debt.

The for-profit sector started out with a cooperative tone toward the Biden administration. This was evident when Career Education Colleges and Universities, which represents for-profit institutions, congratulated James Kvaal, a former Obama official and an architect of the previous administration's efforts to come down on for-profits, on his nomination to return to the Education Department in the top post overseeing higher ed.

In a recent interview, however, a CECU representative had some complaints. The move to cut out for-profit colleges from a Pell Grant increase "is a step in the wrong direction," said John Huston, the organization's vice president of government relations.

The U.S. is still reeling from the pandemic's economic fallout, which has a disparate effect on low-income students, Huston said. Some of them want to advance their career prospects at proprietary schools, and limiting their aid would seemingly run counter to the Biden administration's policy goals of helping disadvantaged populations, he said.

About 54% of students at for-profit colleges in the 2019-20 academic year received Pell Grants, according to federal data. CECU believes Biden's plan would affect roughly 750,000 students.

"This is a blunt instrument with a lot of unintended consequences," Huston said. "We'd rather there be more of a focus on institutional accountability rules and that this provision be taken out."

The National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators also would prefer policymakers address accountability from the side of colleges, rather than involving students, said Karen McCarthy, the group's vice president of public policy and federal relations.

Recent years have seen moves to simplify aid procedures, for instance by reworking the Free Application for Federal Student Aid. Biden's proposal would seemingly upend those efforts, McCarthy said.

The Pell Grant was conceived as a form of portable funding that would follow students to the colleges of their choice. But if maximum funding amounts differ by college type, McCarthy envisions a cumbersome process in which students would need to be informed about the levels of aid they'd receive depending on the type of institution they would attend.

"It establishes an entirely new precedent," she said.

Ideally, students and their families would simply be able to look up how much their award would be, without complicating factors, McCarthy said.

However, often state aid programs provide different amounts of money that hinge on what college students attend, Kelchen, of UT-Knoxville, said. And he didn't anticipate a major burden on the Education Department to enact the change.

But it still is an "enormous policy shift" in that it takes aim at a particular institution type, he said.

Proposal draws mixed reactions

Kelchen wondered how the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, which represents private nonprofit institutions, would react to the proposal, because "a logical next step" would be to curtail aid for private colleges with poor student outcomes.

NAICU President Barbara Mistick praised the new version of Build Back Better in a public statement. Mistick specifically singled out the Pell increase "in a negotiating environment where proposals were being cut or eliminated" and said a plan to make certain unauthorized immigrant students eligible for the grants was important. But her statement didn't address the possibility of different Pell awards for different types of institution, and the organization did not respond to a request for comment.

Many Democratic lawmakers have criticized for-profit colleges. But in a new letter, 13 House Democrats asked their leadership to change the Pell provision, saying that it harms students. They instead called for accountability for institutions.

"Congress has never passed legislation creating this type of distinction in the Pell Grant program," they said. "We urge you not to break from that bipartisan tradition and hope you will ensure that all low-income students are eligible for the expanded Pell Grant."

Higher Ed Dive asked a spokesperson for Sen. Patty Murray, the chair of the Senate's education and health committee, whether she supported the measure.

An emailed statement attributed to Murray did not answer that question. It said that she backed expanding access to higher ed, and that she would "keep fighting until we get this transformative bill across the finish line."

Murray, along with 11 other Senators, in July urged the Education Department to enact tougher rules on for-profit colleges as the agency began redoing regulations governing institutional accountability and financial aid.

Congress earlier this year closed a loophole in what is known as the 90/10 rule, a part of federal law that prohibits for-profit colleges from receiving more than 90% of their revenue from Title IV federal student aid.

But military benefits did not count in that calculation, leading some for-profit schools to seek out active military members and veterans and enroll them for their GI Bill money. The Education Department is currently ironing out regulatory changes to the 90/10 rule.

And last month, the Federal Trade Commission sent notices to 70 for-profit colleges, threatening to fine them for misleading practices, though they had not recently been found guilty of wrongdoing.

Huston, of the CECU trade group, said the public nature of the FTC's announcement "arbitrarily impugned the integrity of institutions."

"When you publish a list like that, you do give the impression something wrong has happened," Huston said.