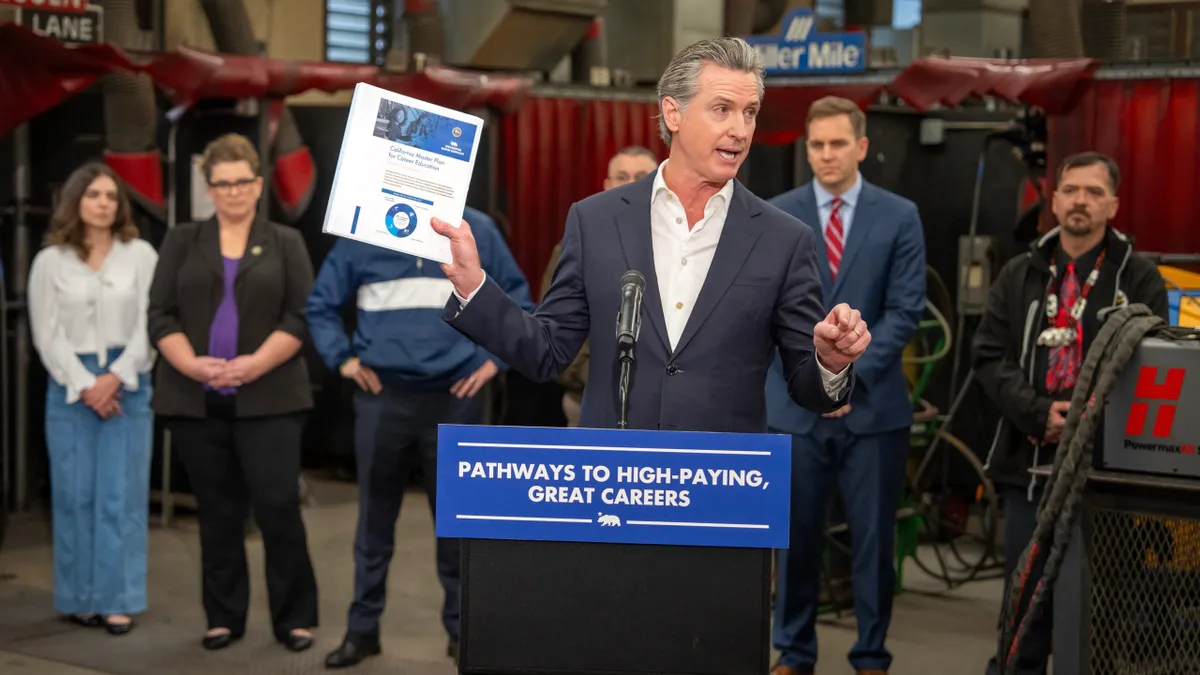

When California in 2019 became the first state to pass a law giving college athletes the right to be paid for the use of their name, image and likeness, it was a strike against the NCAA's longtime prohibition, one the organization said was in place to protect college sports' amateurism model.

Sports policy experts say California's move was a watershed moment, viewed widely as the catalyst that spurred the NCAA to consider its own way to enable student-athletes to get paid for use of their persona.

Subsequent years have seen an explosion of legislation as states grew concerned they would lose student-athletes to schools in states where they could profit, the experts say. At least 18 states have since passed NIL-related laws, and many others introduced bills this year, according to research by The Drake Group, a college sports watchdog.

The result is a jumble of differing state laws with no national standard yet, though several federal NIL bills have been introduced. That could change, as the NCAA expects to vote on a rule of its own later this month. But confusion — and lawsuits — could arise if the NCAA's rule differs dramatically from state law.

"It's a volatile time for the college sports industry," said Ellen Staurowsky, a sports media professor at Ithaca College. "We have to wait to see how all of these things settle out."

Bills, bills, bills

Many lawsuits have put pressure on the NCAA's prohibition on athlete compensation, notably in O'Bannon v. NCAA, which found the organization's policies violated antitrust law. Andrew Zimbalist, The Drake Group's president-elect and a sports economist at Smith College, in Massachusetts, said the NCAA has historically opposed NIL rules because it wanted to hold onto sponsorship money that might otherwise be directed to student-athletes if they had expanded rights.

The NIL campaign picked up steam with California's bill. The NCAA lobbied hard against the measure, going so far as to suggest that schools in the state would be blocked from participating in championship games if it passed. But legislators did not relent and the bill is due to take effect in 2023. Several other states have since passed laws with even earlier start dates — the soonest being July 1 for at least five states, including Florida and Alabama.

States with schools in the Southeastern Conference, a Division I athletic league known for its competitiveness, jumped quickly to pass NIL legislation, said Julie Sommer, an attorney and board member of The Drake Group who tracks NIL-related bills. But state lawmakers nationwide are "eyeing each other's bills," she said, noting that they are popular in part because states do not want to lose their recruitment advantages.

These laws generally have a few common threads, Sommer said, such as that student-athletes should obtain professional representation and that they can't be denied scholarship money if they have NIL contracts. But they're mostly an inconsistent patchwork, she said.

Georgia's, which takes effect July 1, has a unique provision that allows colleges to require student-athletes to contribute up to 75% of their income to an escrow account shared among all student-athletes.

The Uniform Law Commission, an organization that drafts legislation to bring clarity and stability to key areas of state law, also developed a proposal, but it has not been finalized.

NIL has turned into an arms race, Sommer said, noting the situation reinforces the demand for federal policy.

"We need a level playing field," she said.

The federal level

Federal lawmakers have also introduced a bevy of proposals. A few prominent Democratic senators late last year sponsored the College Athletes Bill of Rights, which would ease NIL restrictions and institute revenue-sharing agreements between institutions and student-athletes on money-making teams. A narrower bill from Sen. Roger Wicker, a Republican, would create a framework that allows student-athletes to profit but does not classify them as employees and bans boosters from directly or indirectly paying them for NIL activities.

The issue has held federal lawmakers' attention, and Sports Illustrated reported in May that a bipartisan bill was in the works.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., said during a Senate committee hearing about NIL on Wednesday that "a bipartisan consensus" on the matter "is within reach."

NCAA President Mark Emmert was among the event's participants. He was censured by some lawmakers for not taking up NIL sooner. Blumenthal argued the NCAA had been "hauled, kicking and screaming" to hammer out NIL policies, and only because it feared the uptick of state laws. Emmert did not respond to this criticism during the discussion.

All of the panelists, including Emmert, as well as many of the lawmakers spoke to the need for a federal law.

Wayne Frederick, president of Howard University, said during the hearing that the Washington, D.C.-based historically Black college had a much harder time recruiting student-athletes because the district has no such statute.

In his written testimony, Emmert said operating college athletics within the current "patchwork of state laws is untenable." The many state laws don't allow the NCAA to provide "uniform NIL opportunities as well as fair, national competition," he said. He asked the federal government to provide the NCAA with a degree of protection from future litigation by those challenging its rules.

Federal legislators likely want to act before state laws start taking effect on July 1 in order to avoid confusion among states, Zimbalist said. But he doubts they will be able to pass a bill by that date, given the larger spending debates in Congress.

Still, he's convinced they'll find a compromise. "Nobody believes that the final outcome should be 50 different state bills," he said.

The NCAA's position

The NCAA, meanwhile, has long come under fire for not acting on this issue sooner. Its top governing board voted in October 2019 in favor of NIL compensation, a critical step to the policy becoming an NCAA rule. However, The Associated Press reported that the NCAA hoped to avoid lawsuits from states pursuing their own NIL laws.

Another high-level NCAA governing body, the Division I Council, was set to vote on NIL standards this January but postponed after the U.S. Department of Justice wrote to Emmert to inform him that, as written, the draft rules could run afoul of antitrust laws. The NCAA wanted to have student-athletes disclose NIL activity to a "third party," USA Today reported. But a top Justice Department official feared that the system would be used in a way that could let the NCAA dictate prices for students licensing their NIL, according to the publication.

The Council is once again slated to vote on NIL policies during its meeting later this month. The NCAA noted in a news release that having its rules in place by July 1 would provide "greater consistency" as state laws come into play. The latest public version of the proposal would allow student-athletes to be paid for ventures including promotion of commercial products or services and personal appearances. But it has been criticized for limiting student-athletes' NIL opportunities, including around which companies and products they could engage with.

Because the NCAA's draft rules are more restrictive than those slated to go into effect in some states, it sets up the possibility for the association to sue them. Emmert said during the hearing that the NCAA has discussed filing lawsuits against states with NIL laws. The decision to sue rests with the NCAA's Board of Governors, which is composed of institution presidents.

Also complicating matters is that the U.S. Supreme Court is due to rule soon on a court case, NCAA v. Alston, that would decide whether some of the organization's policies prohibiting athlete compensation infringe on antitrust laws.

Although the case is not directly related to NIL, a decision against the NCAA would permit colleges to offer educational benefits for student-athletes in a pay-for-play system that would further weaken its purported amateurism model, Staurowsky said.

The case, and the passage of state NIL laws, is "reflective of the fact that the NCAA has demonstrated it is incapable of addressing these issues," she said.