Colleges are entering a third calendar year defined by the pandemic.

They had some reason for optimism in 2021, with federal aid and the wide availability of the coronavirus vaccine helping to steady the sector. But the omicron variant threatens their budding stability, meaning some of the operational shifts that emerged early in the pandemic will remain, like campus coronavirus mandates and new admissions policies. Change is on the horizon, however, including possible increases in state support and the Biden administration racing on its regulatory agenda.

We've identified several trends to watch for 2022, and we'll be keeping you updated on them throughout the year.

Efforts to reverse slumping enrollment

With grim enrollment numbers over the last two years, many colleges outside of competitive private institutions and big-name public schools are looking to fill seats. Undergraduate enrollment as a whole plunged, declining by about 3.5% in fall 2021 from the previous year, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. This figure only reflects about three-fourths of reporting institutions, but aligns with patterns throughout the pandemic.

Drawing students back to college will challenge many institutions. The country's economic wounds aren't healed, and two-year schools and some four-year access institutions will see fewer students who can afford college. The strong market for job seekers may also divert some prospective students from schools like community colleges, which have seen particularly devastating enrollment declines.

For other universities, there is heightened competition for the traditional pool of high school graduates. The pandemic essentially sped up trends, including an anticipated drop off in traditional-age college students, that worries admissions professionals. Reenrolling stopped-out students will prove difficult.

Colleges may be able to build on graduate enrollment, which climbed by more than 2% in the fall. And while the pool of lucrative international students dried up and plummeted in the pandemic-rocked 2020-21 academic year, signs point to their numbers now rising. Higher ed leaders have called for a coordinated strategy from the federal government for improving international enrollment.

Can colleges avoid being drawn into a partisan fray?

Political fights are nothing new in higher ed, but 2022 looks to be a year when lawmakers step into colleges' operations to a rarely seen degree.

Diminishing trust in postsecondary education, particularly among the Republican Party, has GOP lawmakers hammering talking points that argue colleges indoctrinate students to liberal viewpoints and create repressive environments hostile toward conservatives. Policymakers and governing boards that have direct ties to the state leaders who appoint them have started to intervene more heavily.

Numerous examples have made national headlines. There was the tenure fight between Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. And there was the inability of the University System of Georgia to secure a permanent chancellor in a search shaded by partisan overtones.

Public systems have been thrown into turmoil by controversial appointees with close ties to politicians, too. Jim Malatras in December decided to resign as head of the State University of New York system following revelations he disparaged a woman who accused former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, of sexual harassment.

Colleges are gearing up for more of these partisan battles. Late in 2021, Republican lawmakers in South Carolina moved to end tenure systems in the state's public colleges. The University of Florida drew investigations from a congressional panel and its accreditor over allegations it suppresses faculty members' academic freedom following a struggle over whether its professors could testify in lawsuits against the state.

Where federal aid and state budgets go

Much of the federal coronavirus aid designated specifically for colleges has been distributed and is starting to dry up. But other pots of federal coronavirus relief funding could still help buoy higher ed.

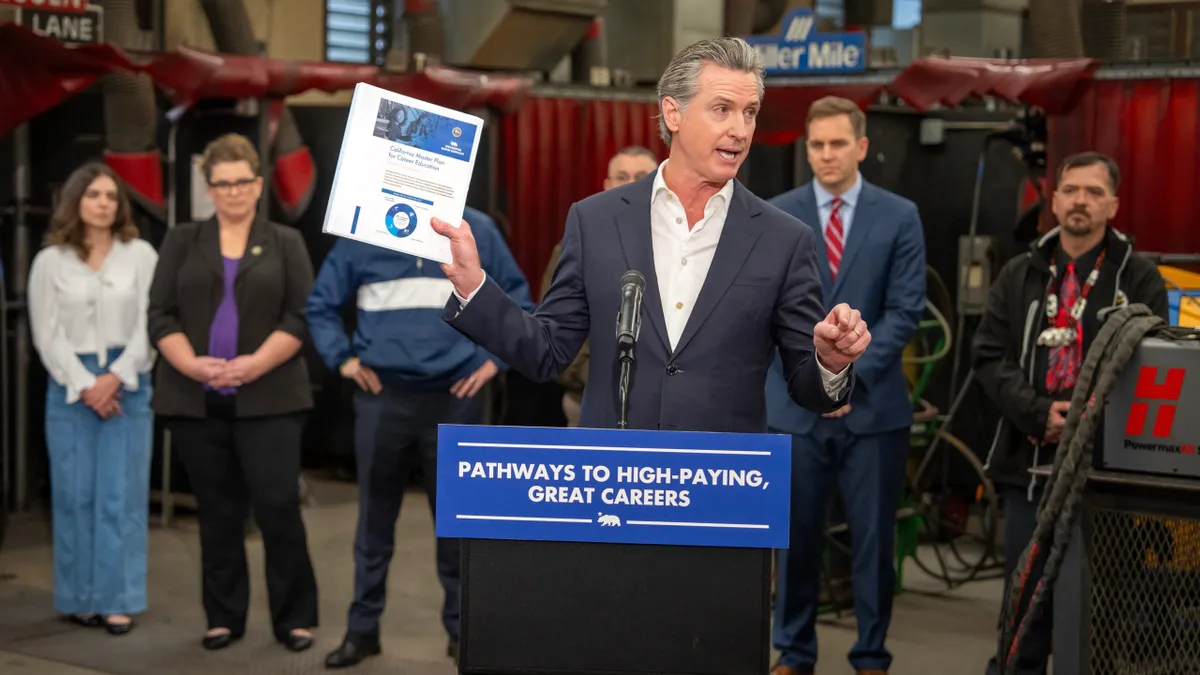

Local and state governments collected a share of the billions of dollars distributed throughout the U.S., and policymakers have fairly wide discretion of how to use this money.

Higher ed has already benefited from the funding. The governor of South Carolina and the governor of Michigan set aside $17 million and $24 million, respectively, for tuition-free college programs. More recently, North Dakota gave $38 million to Bismarck State College, a public polytechnic school, to open a new learning facility.

Experts said colleges should expect to see similar investments in projects that may not have been possible in normal budget seasons.

And because state budgets are stronger, public institutions will likely be making more expansive funding requests. Alabama's higher ed commission recently asked for $2 billion from the state, which would be more than a 17% increase from the current fiscal year's budget. Louisiana's governing body made a similarly high request.

Biden administration plans

Despite not succeeding completely in his legislative priorities, President Joe Biden has progressed on his regulatory policies during his first year in office — although not always at a pace advocates wanted.

The administration started negotiated rulemaking on several policies dealing with the federal student loan system. It also warned for-profit institutions against making false claims to students.

More will come in 2022: The U.S. Department of Education in April plans to release a highly anticipated draft rule governing Title IX, the federal law banning sex discrimination and violence in educational settings.

Advocates for sexual assault survivors have called for Biden to more quickly dissolve the current regulation issued by former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, which they say gives license to colleges to ignore reports of sexual misconduct.

Biden's Education Department will likely look to unravel some of the more controversial parts of the rule, including its mandate that colleges set up a judiciary-style proceeding for evaluating sexual violence cases allowing a survivor and accused student to cross-examine each other through an adviser.

Further scrutiny of for-profit institutions may also come. Biden named James Kvaal to the top higher ed post in the Education Department. Kvaal was noted for helping guide the Obama administration's approach to tackling abuses by for-profit colleges.

How much will campuses need to scramble because of COVID-19?

With the omicron variant of the coronavirus on the rise at the end of the fall 2021 term, many institutions moved to remote operations again. They canceled in-person finals and end-of-the-term rituals, bringing back memories of the beginning of the pandemic.

In the next year, some colleges will face whatever the pandemic brings with limitations put in by policymakers.

Lawmakers and governing bodies in red states have curtailed mask and vaccine requirements. Institutions are pushing their students to get the shot and booster, but some cannot go beyond encouragement. Biden issued executive orders mandating shots for employees that covered colleges, but they quickly descended into a legal tangle of court decisions and injunctions. It's unclear how they'll fare in the legal system in 2022.

It all shows how unpredictable COVID-19 — and human reactions to it — can be. No matter what, it's highly likely institutions will need to be flexible.

Can ed tech providers build on their momentum?

The last two years have been a massive boon to MOOC platforms. The number of people registered on Coursera, one of the most well-known MOOC providers, swelled to around 92 million in September, up from 77 million in 2020 and 46 million the prior year. Likewise, demand for competitor Udemy surged during the pandemic.

Both companies took advantage of this momentum by going public in 2021. And edX, another high-profile MOOC provider, was recently acquired by ed tech company 2U for $800 million.

Although some analysts are skeptical these companies' rapid growth trajectories will last, company executives are confident the heightened interest in online education and alternative credentials will continue beyond the pandemic.

These companies can be seen as competing with traditional higher education providers. But colleges are also working with platforms like edX and Coursera offer credentials, including degrees, at lower price points than they do otherwise.

Testing in admissions

Wide swaths of colleges are no longer requiring SAT or ACT scores in admissions, all but ensuring that test-optional policies will stick after the pandemic.

More colleges will likely extend multiyear experiments they started during the pandemic, which closed testing sites and gave test-optional policies a big push.

Harvard University also extended a test-optional policy through the class enrolling in the fall of 2026. The University of California System scrapped entrance exams entirely in 2021. The California State University system may do the same in the coming months.

A development to watch is whether colleges switch to test-free policies under which they decline to review exam scores at all. Far fewer colleges have tried test-free admissions, but they have still seen growth during the pandemic.

Advocates for restricted use of standardized exams say test-free policies truly provide the more equitable road in admissions that they are seeking. But excising the tests from other parts of higher education — course placement, advising and financial aid — will be trickier than not considering them on applications.

Natalie Schwartz contributed to this report.