Last year, during a Friday morning breakfast meeting, a handful of CIOs discussed how a number of their colleagues had seemingly been overheard whining about how tough the job is — and, somewhat ironically, bemoaning how to find the next generation of CIOs.

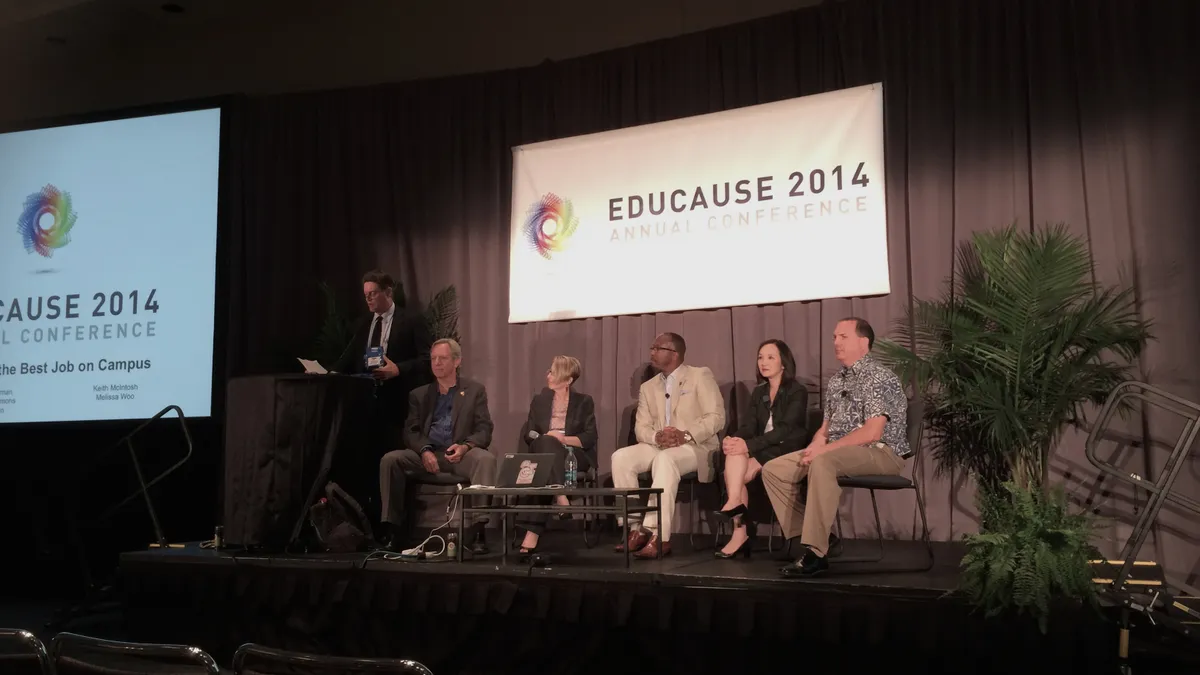

In an Educause panel session last week, CIOs A. Michael Berman (California State University, Channel Islands), Raechelle Clemmons (St. Norbert College), Kyle Johnson (Chaminade University of Honolulu), Keith W. McIntosh (Ithaca College), and Melissa Woo (University of Oregon) set out to set the record straight on why theirs is the best job on campus.

"We're shooting outselves in the foot if we're convincing everybody it's such a terrible job that no one wants to have it," said Berman. "So we wanted to kind of flip that around and talk about what we really enjoy about our jobs and why it's a privilege for us to serve in the roles that we have."

Below are four reasons up-and-coming college administrators should aspire to work in the position.

The job is about collaboration

Among words submitted during a poll of the audience asking what words come to mind when they think of CIOs were "24x7" and "decider." Johnson, however, said the job isn't necessarily always a 24-hours-a-day, 7-days-a-week role, nor is it based so much on making decisions, as it hinges more on "getting all of the right people in a room so we can think about things together."

Added Woo, "I'm a first-time CIO and I think I was a lot more stressed out in my last job, quite frankly, doing operations. In this job, what I love about it is I get to spend all of my time creating relationships, reaching out to people, and finding out what other people do on campus. That, to me, is really, really fun."

Berman noted, however, that the type of person in the CIO role doesn't necessarily turn off the concerns when they leave work, and is constantly thinking about strategy, direction, and how to address issues on campus. For some, he said, the job can become a bit obsessive.

The CIO doesn't have to be a techie

Other words and phrases that appeared during the polling: "tech leader" and "techie."

"I have an undergrad degree in anthropology. I have a master's degree in higher ed administration. I've never taken any formal technology training," said Johnson. "I have worked corporate, but the CIO role, in many ways, is not a technical job anymore."

In fact, he said, a CIO must now be more of a generalist. Backing that notion, Clemmons added that she has a bachelor's in political science and has never taken a technical course in her life — though she did market software. "It really isn't about being a technologist. That's for the folks who work for us," she said. "It's really about being a technology strategist."

Clemmons said that, especially on a small campus, being CIO is about being a change agent and innovator — figuring out how technology fits in on campus. The job essentially offers a diversity of opportunities.

A large chunk of the organization depends on your work

Johnson pointed out that with that diversity of experience comes a "deep impact on a large chunk of the organization." Expanding on that notion, McIntosh stated, "You do get the chance to interface with so many different people across the institution and get to weight in on a lot of strategic discussions that you wouldn't have normally had if you were still in an operational pipeline."

It's a role that affords the opportunity for leadership and vision-setting. "When I think about leadership, it's not just the technology leadership," McIntosh continued. "If you are well-versed in doing your job really well, you're having conversations and you understand and speak the language of your CFO, speak the language of your chief academic officer, learn to speak the language of your faculty, your deans. And once you do that, then you become very much an appreciated strategic leader at the table."

It provides plenty of opportunities for mentoring

Just as important as having a vision for the campus is finding the people who can fix what you have. "In order to be the visionary artist and look at the future — you want to talk about the future of online education, but if no one can use your network, you can't have that conversation," said Berman. "You've got to have the basics working, and you've got to build the team that can deliver."

And that goes beyond just being able to train the team working for you: Teaching faculty how to use the tools provided is key, as well, as it builds trust and respect. "I always say it's a two-strike rule. Most faculty can handle like one technology failure a semester," Berman said. "The second time, it's like, 'You're ruining my ability to teach because I'm walking in the room and I'm looking dumb in front of my students. I can't do my lesson, or if I'm online, I can't meet with them, I can't give the test. They get very upset, and they should be upset ... You've gotta deliver or you won't have trust and you won't have respect."

Would you like to see more education news like this in your inbox on a daily basis? Subscribe to our Education Dive email newsletter! You may also want to read Education Dive's look at 3 things you need to know from Clayton Christensen's keynote on disruptive innovation in higher ed.